Utah law: Gov’t can’t force landlords to provide CO detectors

Jan 18, 2018, 10:43 AM | Updated: Feb 7, 2018, 9:49 am

Free carbon monoxide detectors

SALT LAKE CITY — Fire departments, 911 dispatchers and poison control centers get hundreds of calls every year regarding carbon monoxide poisoning.

In 2015 and 2016, the Salt Lake City Fire Department responded a total of 350 CO-related calls; the Utah Poison Control Center receives 200 such calls every winter.

The colorless, odorless gas is deadly, and the KSL Investigators found little-known Utah law is putting families at risk of being poisoned.

HB402, which was passed by the Utah Legislature in 2009, prevents cities and counties in the state from requiring building owners to install CO detectors in their properties built before 2004. The law passed after Ogden City started requiring detectors in all the residential properties within their borders.

While some proponents of the bill back its passage to this day, others believe it’s a potentially dangerous law that need to be changed.

In Manti, the Cox family narrowly escaped becoming a tragic story. Last winter, KariLyn and her husband, Dallas, awoke to the sound of their 14-year-old son, Korben, collapsing in the kitchen after throwing up.

“I heard him, and it sounded like a thud on the floor,” KariLyn Cox said.

Korben had felt sick the night before, so his mother told him to lie down. Then when Dallas Cox struggled to wake his daughter upstairs for school. She told him she felt strange.

“She said, ‘Dad, I must just be really tired. … I keep waking up on the floor,” Dallas Cox recalled.

The couple never imagined carbon monoxide was poisoning them. But the home’s CO detectors had expired, so the alarms didn’t work and never went off.

“We probably didn’t have much longer to stay in the house before we would have been close to dead,” KariLyn Cox said.

Years before, there was another story that almost ended tragically for a law enforcement officer. Ogden Police Sgt. Art Weloth and his colleagues were investigating the death of a young man inside a home.

“I was talking to one of the other officers on my radio and then went unconscious,” Weloth said.

He survived, but doctors diagnosed him and two other police officers with CO poisoning. A faulty water heater was spewing the poison inside. There were no detectors in the home.

“It was extremely scary for myself and for my family,” Weloth said.

Almost losing those officers pushed Ogden Fire Chief Mike Mathieu to act.

“I was trying to take advantage of the tragedies in other parts of the country rather than wait for our own,” Mathieu said.

It was over a decade ago when Mathieu asked Ogden city leaders to require carbon monoxide detectors in all homes and apartments. State building codes took care of the problem for homes and apartments built after 2004, but 90 percent of Ogden’s homes were built before then.

Mathieu believed the rule would save lives, but city council minutes show not everybody agreed. The Weber North Davis Association of Realtors and Utah Apartment Association fought it.

“It lacks common sense,” Mathieu said. “It’s very difficult to enforce such a confusing principle that you, as an occupant, have to provide a carbon monoxide detector. But you as the occupant can ask the landlord to provide a smoke detector.”

The fire chief won that round, and Ogden passed the proposal.

But the Utah Apartment Association didn’t give up. In 2009, they took the fight to the Utah Legislature and, this time, the landlords won. Lawmakers passed HB402, taking away a city or county’s ability to require building owners to install carbon monoxide detectors, overruling Ogden’s city law.

As a result, anyone who rents a home in Utah must bring along their own CO detector — it’s not the landlord’s responsibility.

At the time, lawmakers applauded themselves. Then-Sen. Michael Waddoups, R-Taylorsville, said: “Senator (Sheldon) Killpack, I would just insert this is the responsible thing to do, and it also puts the onus on the person who’s responsible for it, so I commend you and the sponsor.”

To this day, the Utah Apartment Association stands by the law.

“We think the occupants being responsible is the way to go,” said Paul Smith, the association’s executive director. “The owner is not there, the occupant can disable them, they can remove them.”

According to its own website, the association doesn’t want cities or even health departments to require landlords to fix up older properties with carbon monoxide detectors.

“In 2009 we were in the middle of the great recession. And when a city requires an ordinance that might impose additional costs per unit, we thought that was just the worst time to have a city imposing additional costs,” Smith said.

Mathieu believes the law was a mistake.

“When someone important enough dies here in the state of Utah, the law here will change just like it did in Colorado, just like it did in many different parts of this country,” he said.

Back in Manti, the Coxes believe safety should come first.

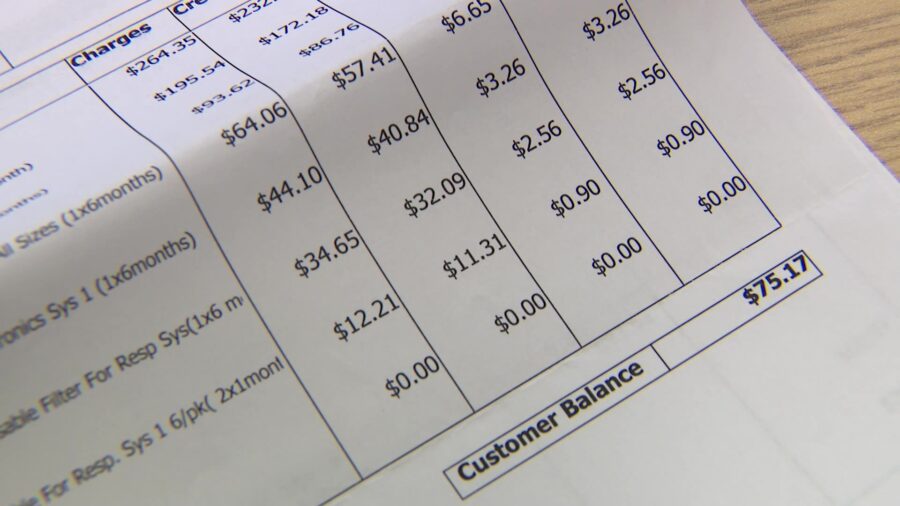

“It’s so scary,” KariLyn Cox said. “Even just the costs — the medical cost — is really expensive to go through.”

Since HB402 became law, U.S. Census records show the number of renters moving to the Salt Lake City metro area spiked. It also shows most renters live in buildings built before construction rules began requiring carbon monoxide detectors. The data show new construction hasn’t caught up.

Rep. Mark Wheatley, D-Salt Lake City, said he plans to file a bill to rescind the 2009 law.![]()