Frontline health care workers say they’re burned out, experiencing staffing shortages

Sep 9, 2021, 9:52 AM | Updated: 10:00 am

LAYTON, Utah — No one’s taken the brunt of the pandemic like health care workers on the frontline. The unrelenting cases of COVID-19 have brought many to their breaking point. Three caregivers at Layton Hospital are sharing how their job affects them personally.

Eighteen months later and they’re still showing up for work to care for patients with COVID-19.

“So I think initially, I was kind of excited to be a part of that,” said Adam Young, a registered nurse who works in the medical/surgical and ICU unit. “To be able to say, ‘Man, you know, in 2020, 2021, I’ve been able to care for these patients through the pandemic.'”

But Young said that excitement has now been replaced by fatigue and grief. He said it’s challenging not knowing what to expect going to work each day.

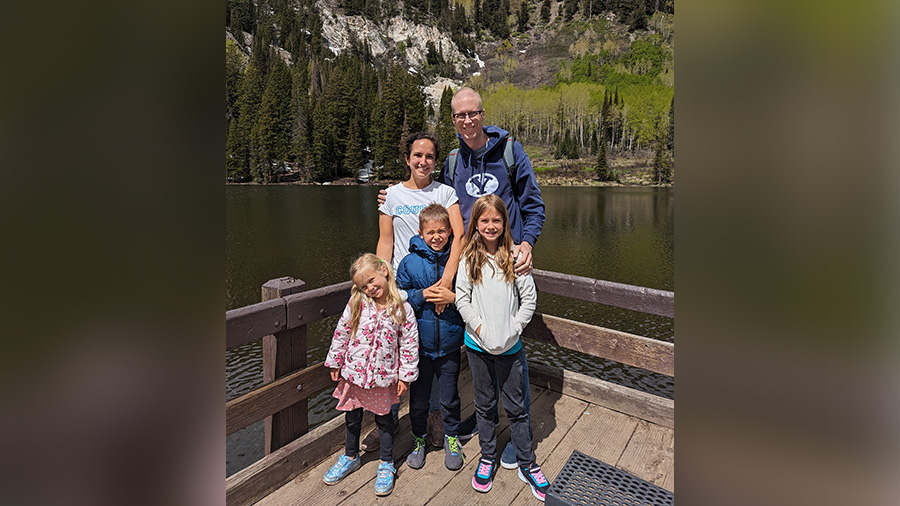

Intermountain Healthcare nurse Adam Young says he’s burned out and has been pushed beyond his limits recently as he’s continued to care for an increased number of COVID-19 patients. (Photo Credit: Adam Young)

“Waking up and wondering, ‘Am I going to have to hold a dying patient’s hand,’” he described through tears. “To hear somebody my age FaceTime their family and say, ‘Hey, I’m being intubated. I don’t know if I’ll ever see you again.’ Those are gut-wrenching conversations that I have to hear.”

Young added he’s burned out after months of extreme levels of care.

“How much can I push myself? You know, what’s my breaking point? I still want to give the best care that I possibly can. I know what I signed up for as a nurse and I’ve pushed myself to that limit and beyond,” he described.

Respiratory Therapist Jenelle Waite feels the exhaustion too. “I have experienced quite a bit of compassion fatigue,” she said.

In her 12 years as a therapist, she’s never felt so discouraged. “It’s disheartening,” she said. “A lot of the time, they don’t get better like we expect them to and it’s been really hard for me as a therapist to watch patients decline.”

The recent surge in hospitalizations has her fearful she won’t be able to adequately do her job. “There are only so many of us, we can only be in a couple places at the same time,” Waite said. “I worry that we might not be able to make it in time for someone that needs our help.”

“It’s just this huge behind the scenes shuffling that we’re doing trying to provide adequate coverage,” she said.

Dr. Cabe Clark manages a group of about 30 physicians in the emergency department at Intermountain Layton Hospital. “Some of the hardest things are to see how stressed the team is in the E.D.,” he said. “It’s overwhelming at times.”

Three Intermountain Healthcare caregivers at Layton Hospital expressed exhaustion and burnout personally and for their staff after caring for COVID-19 patients for 18 months now. They say the recent surge in more hospitalizations has only added to the stress. (KSL TV/Josh Szymanik)

He feels responsible for taking care of his team. “You kind of feel like a parent that has a sick kid, right? You can’t really do a ton, you want to help them, but you kind of feel like your hands are tied sometimes. So it’s, challenging,” he added.

Clark sees the consequences firsthand. Recently, at McKay-Dee Hospital, he said the team had to shuffle resources around to meet the demand of their patients. “We had eight nurses who called in sick for over a 24-hour period,” he said.

Two nurse managers who had already worked all day left their families to come back in the evening. “And both of them were like worked to the point of tears, but they had to come in because there was no alternative,” Clark said.

Clark is one of the physicians who went to help in New York last year. He said one of the most frustrating parts of his job is not being able to provide the help patients need quickly enough with limited resources, both personnel and equipment. “We’re maxed out — at capacity,” he said.

The demand has only increased in recent months. “Then to have the ER saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got not one, not two, but three or four patients that we need you to admit,’” Young said. “Where do you want me to admit them? The nurses already have more patients. So we’re being asked to take even more above what we normally would.”

Utah is not immune to the health care shortages the country’s facing nationwide. “I think it’s taken its toll and that’s why we’re short-staffed,” Clark explained. The thought of quitting crosses Young’s mind often. “(It’s) a daily thought. I get emails on a daily basis on open positions throughout the country … for another job that’s, you know, less stressful,” he said.

He said separating work from family life is hard. Young and his wife have a 3-year-old son.

Adam Young is a nurse on the medical/surgical and ICU unit at Intermountain’s Layton Hospital. He says it’s hard not to bring the stress of work home to his family. He and his wife have a 3-year-old son. (Photo Credit: Adam Young)

“The emotional, mental, physical exhaustion from being so burnt out — I know it affects my family,” he said. “When I go home from work, I just want to lay down, I just want to relax, and I’m probably a grouch to be honest with you. I’m probably pretty short with my family and that tears me up because I want to be a loving husband and a loving dad.”

Clark said his work is a constant topic of conversation in his home too. “It’s tough, I have a couple kids in high school and two in junior high,” he said.

Though Waite knows she is protected by her PPE gear, she fears she will bring COVID-19 home to her children who are too young to be vaccinated. “I am in a position where I’m highly exposed to COVID-positive patients,” she said.

They each urge people to get the COVID-19 vaccine. “I care for predominantly unvaccinated patients,” Young said.

Though Jenelle Waite knows she is protected by the PPE gear she wears, she still fears she will bring COVID-19 home to her children who are not old enough to be vaccinated yet. (Photo Credit: Audrey Kay Photography)

“They all will look at me and tell me that they wish they would have got the vaccine,” Clark added. “We respect their choice, whether we agree with them or not, but it’s at that moment or when they’re sick and they’re in the hospital so many of them regret that decision.”

“I just wish the public could look beyond what their neighbor says and look at the data, look at the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine,” Young said.

They also remind people to show extra love to health care workers.

“Treat us with respect, treat us with kindness,” Young asked. “Please don’t take it out on us. I’ve been chewed up one side and down the other by family members.”

“Support them and make sure they’re doing OK because it’s been a really hard time for all of us,” Waite said.