KSL+: Looking back at long term impacts of 9/11

Sep 9, 2021, 4:38 PM | Updated: Sep 10, 2021, 11:53 am

Matt Rascon: This week on KSL+…

Erica: Helpless, I just remember seeing replays of the planes crashing into the World Trade Center,

Matt Rascon: the 20th anniversary of 9-11.

Juliann: That really left an impact. I left a mark on how we do things.

Matt Rascon: And the team at KSL this week has been looking at the lasting impacts of the tragedy.

Omar: I think people automatically assume that Oh, like, he’s from there, you know, and he’s one of them.

Matt Rascon: How did it shape us? How has it changed the way we respond to a crisis?

Omar: People would shout things, maybe walking down the street, and someone would shout something out of the window,

Matt Rascon: What could we have done differently?

Peter Roady: We didn’t really take full advantage of those windows of opportunity. And I think that is actually an added tragedy of September 11th.

Matt Rascon: A day that simultaneously brought us together and tore us apart. repercussions were still feeling as we face COVID, and a host of other political climate and racial issues. I’m Matt Rascon. And this is KSL+.

Avais Ahmed is the founder of the Utah Muslim Civic League. At age five, he and his family made their way from Pakistan to Kaysville.

Avais Ahmed: As I get older, I do find that it was challenging because a lot of kids, I was one of maybe eight minorities in my graduating class of 700, 800. So a lot of kids were very curious about me. And so they would ask, Hey, like, what’s this obscure, you know, religion that you’re a part of? And they thought that, hey, we live that the Latter-day Saint faith is, you know, a very majority population, which is in that area, they had no idea that Muslims, you know, [are 1.6 billion] plus people,

Matt Rascon: Ahmed was in the Student Union at the University of Utah on 9-11.

Avais Ahmed: Muslims are portrayed on the news, and especially for me, it was very heartbreaking that to the general public, Islam was really introduced through 9-11. And so you know, it’s like, if Warren Jeffs introduced the Latte-day Saint faith to people, you know, it’d be a very painful thing, because that’s somebody that we don’t even you know, accept as representing the values of Islam, not one iota. So I remember and then they’re, you know, showing, you know, sama bin laden with a beard and other things. And at that point, I had a very sinking feeling that, okay, this is going to be something that, you know, people are going to ask, you know, what is Islam and in a very negative way, it was going to be misrepresented to them. And now, I mean, obviously, since then, it’s, you know, anytime something happens, we, as a Muslim community, we, we were scared that, hey, you know, this is going to be somebody from, you know, that part of the world or that extremist background, and then it’s going to be another trauma we have to relive. And we have to tell people again, that hey, this is not, you know, part of our faith.

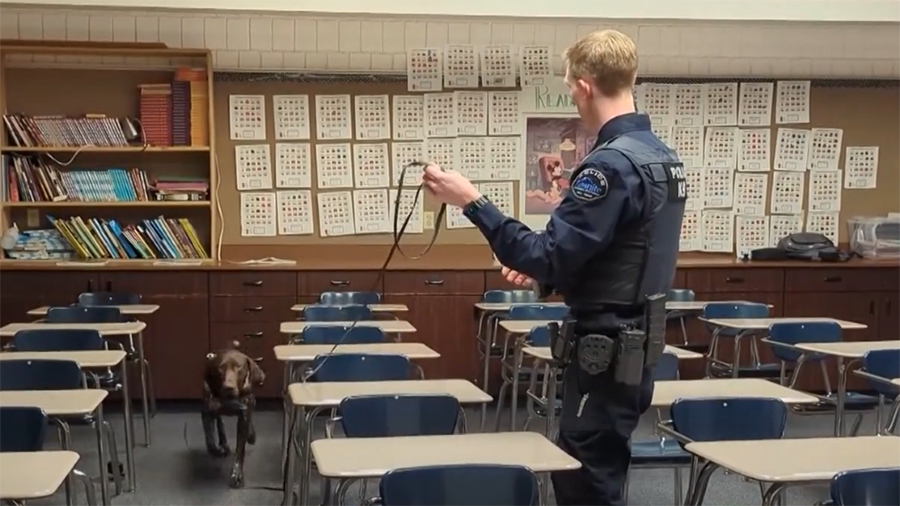

Matt Rascon: And for Muslims in America, what they faced in the United States after that day went beyond individual abuse and discrimination. In 2020, Vice reported the US government was buying data on millions of users from apps designed for Muslims, a dating app, a prayer app, and more. From 2002 to 2014, the NYPD use police informants, plainclothes officers, Video Surveillance, and more to watch Muslims in their community. Kelsey Dallas from the Desert News wrote about how 9-11 had a different impact on many American Muslims.

Kelsey Dallas: It’s difficult to understand just how common surveillance of Muslim groups became after 9-11. I think those of us who weren’t affected by it might assume, oh, if there was a spy sent in or if there was a camera setup, that must mean that the government was hot on the trail of something really dangerous taking place. But in many cases, it was much more random than that. It was just like, okay, here’s a mosque let’s try to watch it or, Hey, I know this Muslim person, what if I asked them about sort of becoming a watcher of their community. And so in some of these religious freedom cases, judges have pointed out that it just felt as if there was no original justification, other than 9-11, the generic sort of terrorist threat. And then in some cases, it was actually shown that the government was retaliated against someone who had refused to spy on their Muslim friends and family members. And that’s why they ended up on the no-fly list–they weren’t cooperated with the government. And so again, this came from, in the government’s mind, a place of trying to ensure safety and trying to be really proactive to ensure that we didn’t see damage the scale of 9-11 ever again. But it just led to some really frustrating, heartbreaking situations. And one of the Muslims that I heard from through this piece, she was talking about how you sit in your house of worship, this place that supposed to be a place of peace, a real comforting place for you to be and you were just nervous and afraid, and you didn’t know how to talk to the person next to you because it felt like this suspicion had infiltrated every part of your life.

Matt Rascon: It’s called “How 9-11 Changed American Muslims’ Relationship with Religious Liberty.” Talk about what led you to that headline?

Kelsey Dallas: Absolutely. So when I thought about what I could contribute to the Deseret News’ 9-11 coverage this year, what jumped out to me is how many important religious liberty lawsuits have taken place in the past two decades involving Muslims. And these were cases where Muslims were pushing back against government surveillance, discrimination by the government discrimination by everyday American citizens. And I wanted to sort of trace how those all related to the 911 attacks.

Matt Rascon: What did you find? I mean, you kind of follow a few different characters in there. What did you find from these interviews and the panels that that you listened in on?

Kelsey Dallas: I think it’s clear that because of the mourning and grief and frustration and anxiety that grew out of the attacks on 9-11, the American country’s relationship to its Muslim citizens really changed that day, there was concern about sort of our Muslim neighbors and what intentions they had. And that that really wasn’t fair. But that doesn’t mean that you can shake it overnight. I mean, there were people who just didn’t understand Islam. And so we I just think it’s fair to say that we’ve really been struggling as a country since then, to say, how do we apply our religious freedom protections to this situation and trying to work out a more peaceful future of our peaceful relationship with Muslims here in the US. One of the things I’ve tracked in several different stories is that there’s always this natural fear between different faith groups or between different groups of Americans in general. And so Christians are naturally sort of nervous about Muslims, Christians are naturally sort of nervous about non-Christians in general. But when something like the terrorist attack happens, it just takes that fear to a new level, a new level of concern. And so there’s been a lot of work to try to combat that. Because that fear doesn’t really come from reality. Sometimes it’s just this instinct in ourselves that says, that person is different from me, I’m scared about how they will affect my group. And so now as a country, we have to sort of take a step back and say, how do we combat that instinct that leads to some mistreatment of American Muslims, and then work together to repair some of the relationships that’s been damaged in the past two decades.

Matt Rascon: Yeah. And we’re not just talking about individuals, you know, who are just pushing back on Muslim neighbors, but you’re even talking about, you know, the government involved here and surveillance and things like that.

Kelsey Dallas: Unsurprisingly, the 9-11 attacks led to an increased interest in our national security apparatus. And so there was a lot of funding put in to tracking suspected terrorists around the world, but also surveillance efforts here at home. That led to some really difficult situations for American Muslims in their mosques, because there would be spies sent into the mosque to track what was going on. And I mean, really, no evidence would often emerge from that; it would just serve to make that mosque environment much more difficult to be part of it. So their house of worship, but really be infiltrated by the fear and anxiety of the government and of other citizens. And then the other type of case I talked about in my story is that there’s been a lot of pushback to Muslim efforts to build new houses of worship, mosques, in communities across the country, and the local zoning boards, and then the maybe the town leadership, and then the state leadership, and then it goes all the way to the government is trying to prevent these Muslim groups from getting the permits, they need to build a new house of worship, if they’ve outgrown their old one,

Matt Rascon: It seems critical to differentiate between the extreme side of a religion that encourages violence, because as we saw in Afghanistan, thousands fleeing the country, once the Taliban came into power.

Kelsey Dallas: And many of those people are Muslims themselves, because it’s important to remember that when there is a Muslim group that comes to power, it has a bone to pick with other Muslims just as it threatens Christians and members of other faith groups as well. And so I think that’s something that we forgot in the aftermath of 9-11 is that there are many different interpretations of Islam. There are many different ways to sort of rule as a country with a close relationship to Islam. And that’s something that we’re still having to remind people of, to this day that there’s many ways to be Muslim, just as there are many ways to be Christian and many ways to be non-religious.

Matt Rascon: I think you’ve touched on this a little bit, but it is natural, you know, to be more suspicious and things when you’re hearing in the news about the extreme side of one religion, how is it being treated differently in the US and others?

Kelsey Dallas: Well, as I put out my story, and this is not a new phenomenon, that a faith group that isn’t that well known, or that is somewhat new to a country would be treated with suspicion. And so in the past, there was aggressive pushback against Catholic immigrants to the US, for example, of Latter-day Saints were sort of driven out of the middle of America. And that’s how they ended up in Utah because of religious persecution. And so it wasn’t as if everything was hunky dory. Before 9-11, there was a lot of concern about Muslim Americans, what people curious about what their religion was all about. But what happened after the terrorist attacks was that people who weren’t familiar with Islam or didn’t know someone who’s a Muslim, just assumed that Islam equal terrorism, or that Muslims equaled a threat. And it was, like I said, a very broad brush. And so you went from this baseline fear or confusion or concern to just this very aggressive, like, my life is at risk. And so now, how do we as a country take a step back and say, That’s not fair to equate Islam with a terrorist system, or with a dangerous set of politics, we need to sort of take this on an individual basis and treat our Muslim neighbors as neighbors truly.

Matt Rascon: And how do you? I mean, how do you, you know, call for religious freedom and equality for one religion, while ignoring it for another?

Kelsey Dallas: I think that a lot a lot of people miss that. Well, that’s certainly a theme that emerges in quite a few of my stories that sometimes the fiercest advocates of religious freedom, in one context, are the first people to say we should take it away from others in another context. And that’s really not a way to operate. If you’re going to be for religious freedom for yourself, you have to fight for religious freedom for all. And so, again, that’s another sort of lesson to return to in this moment and to remember, as we move forward,

Matt Rascon: Is there anything else you can say about what those you talked to and heard from are continue to deal with day to day and sort of the fight?

Kelsey Dallas: There are lawsuits that are still ongoing, the Supreme Court will actually hear one this fall about, in cases that involve surveillance. At what point is the federal government allowed to invoke what’s called a state secrets privilege and sort of refuse to let on what it knows about people are why it was watching people? And so that’ll be really important, just to think about how we operate as a country when it comes to surveillance. And then in general, I think the Muslim community is using the 20th anniversary of 9-11 to say, Okay, here’s what we’ve experienced the past two decades, here’s what we’ve achieved in some of these important lawsuits. But how can we continue to have a positive effect on our society moving forward? And how can we share the lessons we’ve learned with other groups that are facing persecution or dealing with difficult situations? And so I actually think this story ended on a very positive note, which is how the American Muslim community is trying to build up other groups that are similarly anxious about their future.

Matt Rascon: Okay. Kelsey Dallas, reporting for the Deseret News on religion for many years now. Thank you for your time, appreciate it.

My colleague Peter Rosen, interviewed Bishop Scott Hayashi, the current Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Utah, about his views on how the US is still dealing with the consequences of that day.

Bishop Scott Hayashi: The question I asked about, about the effect of 9-11 on the United States of America is one that I certainly considered and thought through and meditated on, over and over again. I personally believed that we had a moment when we could have turned in a different direction and done different things as a nation. Instead of going to war, we had the goodwill, of the most of the rest of the world. The President of France, made the statement, we’re all Americans now.

We had the empathy from so many places around the world. And we could have seized on that, to reflect, to reflect upon our own self as a nation, about our place in the world.

And, what response could we make? You know, I was in New York, a week after 911. And I walked around the city, you might recall, they had these shrines set up in front of stores, with candles and photographs of, of people who worked in the Trade Center, people who are missing still. And talking with the people in New York Cityabout what had happened in it, and what I heard over and over again, in the midst of the shock, and was a deep sense of, again, of sorrow. And also, what I actually did not hear in the people whom I spoke was any talk of revenge, or vengeance. That never came up in those conversations. In fact, the opposite came up, which was stated like, why would we want to do what happened to us to somebody else? It’s horrible. Why would we want to subject anybody else to what we just went through? So I believe we had a moment when we had an outpouring of compassion from most of the world. But instead, as we all know, we went back into war.

And I believe that what happened as a result of, of 9-11 is, we became a much more anxious nation, much more reactive than we had been. We are shocked out of this feeling that because we live in United States, and we were separated by others, by oceans, that nothing could ever happen to us. And so I think we became more fearful, as a nation, I think we still are. And I also believe that when people are fearful, and anxious, that we behave in ways that we might not otherwise behave. Because when people become anxious or fearful, we tend to seek out a reason for that. And we tend to seek out a container that might contain our fear and our anxiety. And the way in which we do that tends to be we place it on some other people we placed on people who might be different than ourselves. We look, we look to find somebody to hold responsible for this. And they serve as container for that period anxieties, we can concentrate all of that into some of the group of people. And in the United States, I think what we’ve done is we’ve done that by looking at each other to find out who we can use as the convenient scapegoat that if only we could get rid of them, we’d be better off and I trace a lot of that back to 9-11. We I think we have still not ever dealt with, as a nation, the trauma of that.

As a person of faith, I continue the belief, I continually believe that with the help of God, we have the possibility of actually moving forward together in a healing way, and I don’t mean by that, that we pretend as if we’re all the same. But I believe that what we have, though, hope and possibility of doing is actually teaching one another, how to listen, how to actually be in relationship with people who simply disagree with the way you or I might think, or believe or vote. That, that there is the possibility that if we could learn how to see each other as made in the image of God–is how I would state it as a religious person. And if one is not a religious person, the way to say, to see each other as human beings, has persons who have value and then to learn how to be able to engage in, in relationship and conversation, which doesn’t seek to prove the other wrong, but seeks to understand the world from the other person’s point of view.

So I might say to a person who is completely opposite, let us say, of the way I am, and the things I believe, and to simply ask the person not to justify why they think this way or, or believe this way. But to ask the person what brought you to believe what you believe. Not to criticize, but to understand, what were the factors in that person’s life that that brought this person to where he or she is today? Without any asking of how in the world can you possibly think this way, but to try to understand and then perhaps, then that person might be open to hearing why I am the way I am. And to see when each other a common humanity in the midst of, of life experiences which have impacted us and brought us through different places. And I believe that only if we can, if, if only we do that. Or if we don’t do that, I don’t really have much of a chance, frankly. Otherwise, it’s too easy. It’s just too easy to keep the other person as somehow less than me, or different than me, and therefore not as much have as much value as me are to conveniently keep the person as the reason why things are as terrible as they are. But I believe there are moments of grace and beauty in the midst of all of this life we’re personally living and, and to continue to look for those moments that you’re trying to glimpse where God might actually be present in those moments. And to celebrate those as opposed to drawing constantly on the latest outrage.

Matt Rascon: That does it for us this week here on KSL+ I’m Matt Rascon. We’ll see you again next week.