Players ‘targets.’ Victims ‘glamorized.’ Lawsuit highlights secret USU football team recordings about sexual assault

Dec 14, 2021, 11:18 PM | Updated: Jun 19, 2022, 10:00 pm

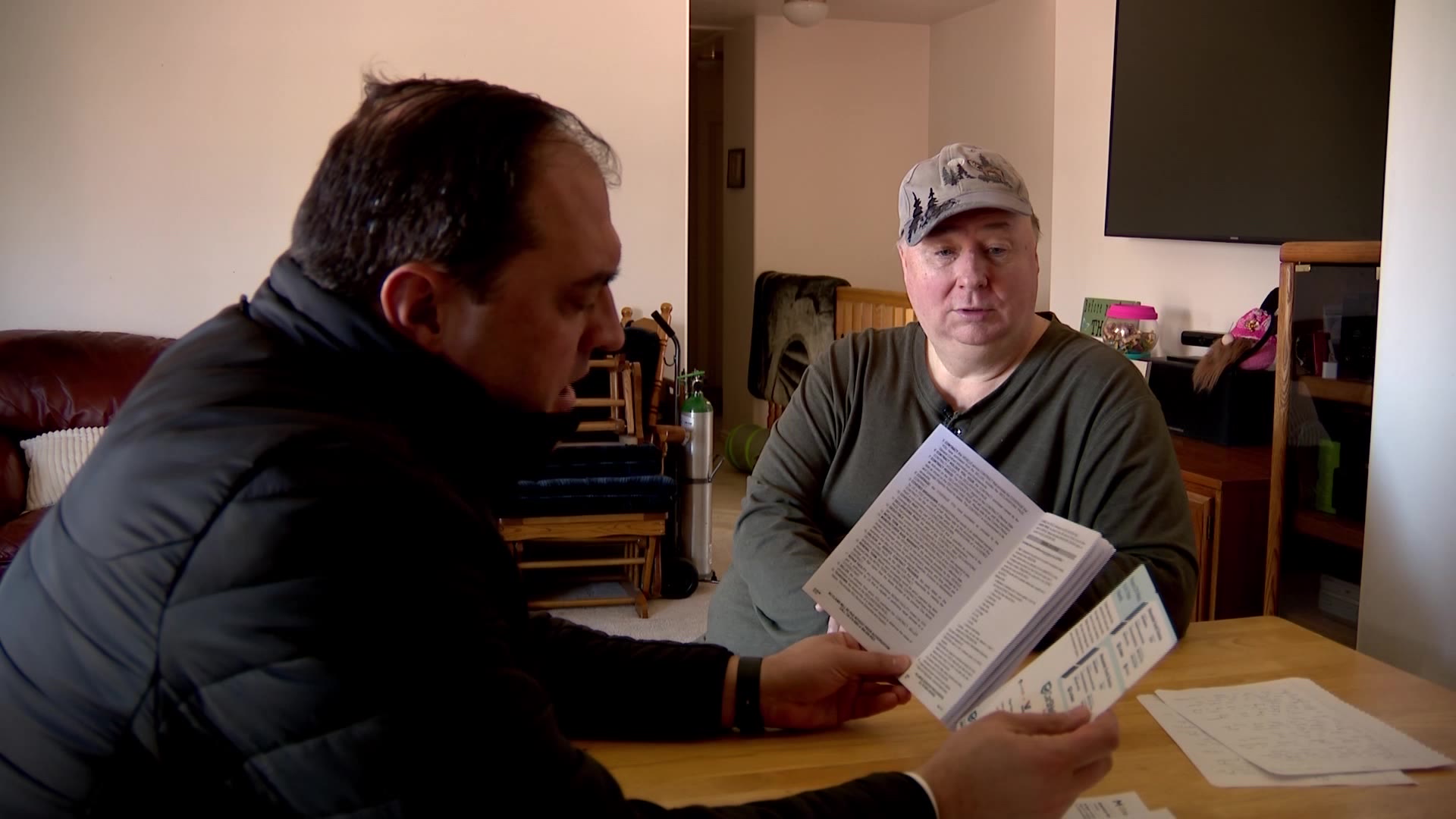

SALT LAKE CITY – By August, Kaytri Flint had little hope that Utah State University would sustain her allegation of rape against a football player at the school.

It had been almost two years since she first asked the university to investigate her claim and the case was still dragging on.

Then Flint learned about a recent recording of the university’s police chief warning the USU football team that Latter-day saint women may falsely report rape.

“How can I trust in them when they’re saying these things?” the 22-year-old sociology major remembers thinking.

The recordings are now part of her gender discrimination case against the university.

Flint sued USU Tuesday in federal court in Salt Lake City, alleging it has not made good on its promises to do better after a 2020 U.S. Department of Justice report found reports of sexual assault went unaddressed on the Logan campus.

KSL does not typically name victims of alleged sexual assaults. Flint wanted to use her name. She contends the school continues to favor male athletes accused of sexual misconduct – echoing a finding in the Justice Department report – and says it has flouted recent changes in guidance from the U.S. Department of Education.

The university is “still failing to uphold its obligations under Title IX,” her lawsuit states, referring to the federal law barring sex discrimination at schools.

Secret recordings

The lawsuit points to secret recordings of a meeting between the football team and police, and another between the football team, the school’s Title IX coordinator, and a victim advocate as key evidence. The meetings occurred in August, according to Flint’s lawyers.

In audio of the meeting with law enforcement, obtained by KSL, USU Police Chief Earl Morris is heard telling the team that they live in a “Mormon community” and women may regret having sex after the fact, which he says may motivate them to lie to their faith leaders. His comment is met with boisterous laughter.

“Oftentimes it’s easier to say, ‘No, no, no, that wasn’t consensual,’” he said. “Be dang sure of who it is that you’re having consensual sexual relations with.”

The warnings came during a larger conversation with players about staying on good terms with the police.

Donna Kelly, a retired sex crimes prosecutor, told KSL that false claims of sexual assault are just as rare as they are for other crimes. Research from the FBI has shown that 2%-8% of reports are false, said Kelly, who worked in the Salt Lake County District Attorney’s Office until October.

Many victims don’t come forward, and those who do are often met with doubt or even ridicule, harming their ability to recover and heal, Kelly said.

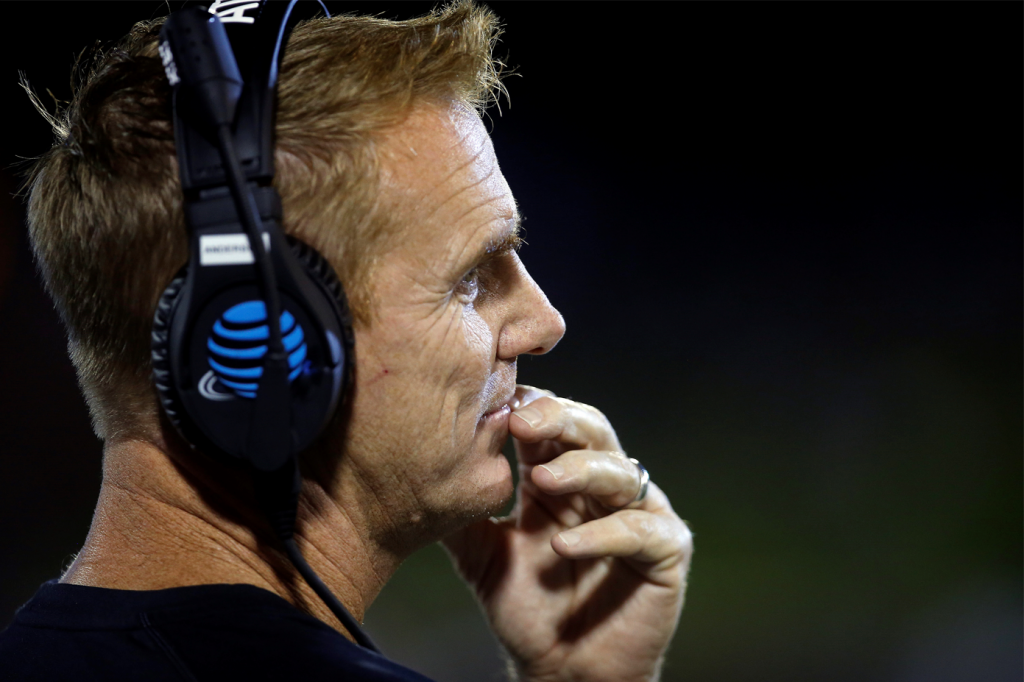

In a separate meeting with victim advocates, USU’s football coach, Blake Anderson, is heard saying it “has never been more glamorized to be a victim,” according to Flint’s lawyers, and that the football team is a “target to some.”

“In my experience with working with thousands of sexual assault victims, it is not a glamorous experience,” Kelly said. “It is devastating.”

KSL’s requests for comment from Morris and Anderson were referred to the university.

In an email, USU spokeswoman Amanda DeRito told KSL Investigators, “The transcribed statements, as presented in the lawsuit, are not consistent with the university’s trainings or values on this matter.”

Title IX investigation

Under Title IX, colleges are tasked with investigating and resolving sexual assault complaints from students, whether the conduct happened on campus or somewhere else.

The administrative process is separate from police investigations – although both can occur at the same time — and considers whether school policy was violated.

Flint says an initial school probe and an appeals panel found her report to be credible. But she then endured five months of silence after the findings were sent to USU President Noelle Cockett for review.

In December 2020, Cockett sent the case back to the school’s Office of Equity to be reinvestigated, citing due process concerns for the student-athlete.

“I was like, yeah, they’re protecting him, because he’s a football player,” Flint recalled thinking.

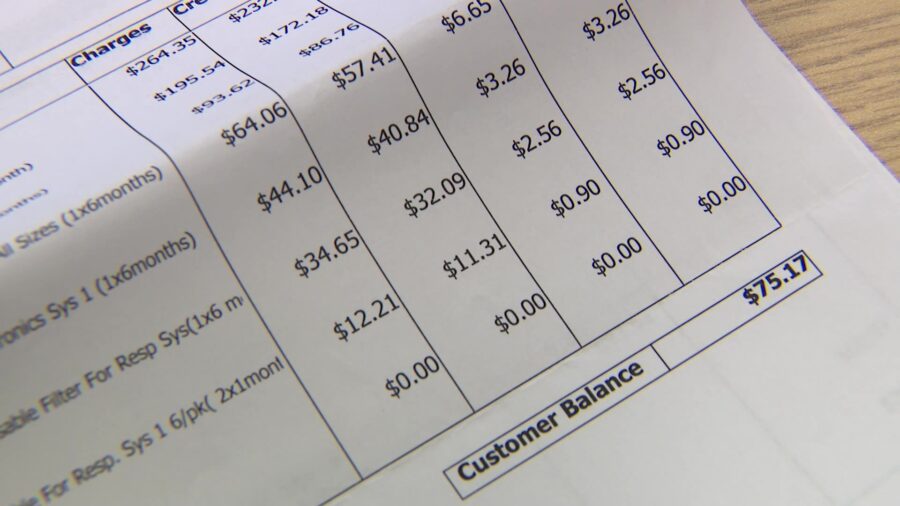

The office restarted her investigation using out-of-date federal standards more favorable to the accused, Flint contends. Her assailant was still allowed to play football as her case dragged on, according to her lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court.

Title IX investigators in the office set new rules, adhering to a short-lived Trump-era requirement that placed a greater burden on victims, subjecting them to cross-examination, and only allowing evidence if the person who provided it agrees to testify.

Daniel Carter, a national Title IX expert, said the beefed-up standards only applied to newer cases, not Flint’s 2019 report.

“In my opinion, it is inappropriate for a school to change the rules in the middle of a proceeding,” Carter said. “You don’t right an injustice with another injustice. You make it just for everyone involved.”

Flint said the process became overwhelming.

She recalled a Title IX investigator telling her at one point that “it would probably be easier if you left the school.”

According to the lawsuit, the school’s Title IX coordinator put the burden of tracking down evidence on Flint, even asking her to obtain photos of her injuries taken during her sexual assault exam. The investigator said the male athlete accused of raping Flint had requested to view the “highly sensitive and personal photographs,” court papers say.

KSL spoke with an attorney who has represented the male student in the past. She declined to comment.

Flint decided not to participate in another administrative hearing, and the school ended its investigation.

“I’ve lost days of my life, trying to prove to them that I’m worthy of protecting, that my experience matters, and that it hurt me, that I’m not OK,” Flint said.

Steps toward change

DeRito, the university spokesperson, said students involved in misconduct cases have faced delays because Title IX regulations have changed twice in the last two years and the school’s Office of Equity has had a high rate of turnover.

“We have been working diligently to address these issues and will continue to look for ways to improve our sexual misconduct grievance process,” DeRito said in an email to KSL Investigators.

She pointed to steps the university has taken to better prevent and respond to sexual misconduct, like requiring trainings for students, hiring two new employees to help students seeking support, and bringing on a victim advocate and detective in January 2020 to respond to sexual crimes and domestic violence.

“That said, we know cultural change takes time; students and employees bring their own developed perceptions and beliefs around sexual misconduct with them to our campuses,” DeRito said. “USU stands firm in its commitment to create a campus culture where individuals understand and practice sexual respect and survivors of sexual assault are supported.”

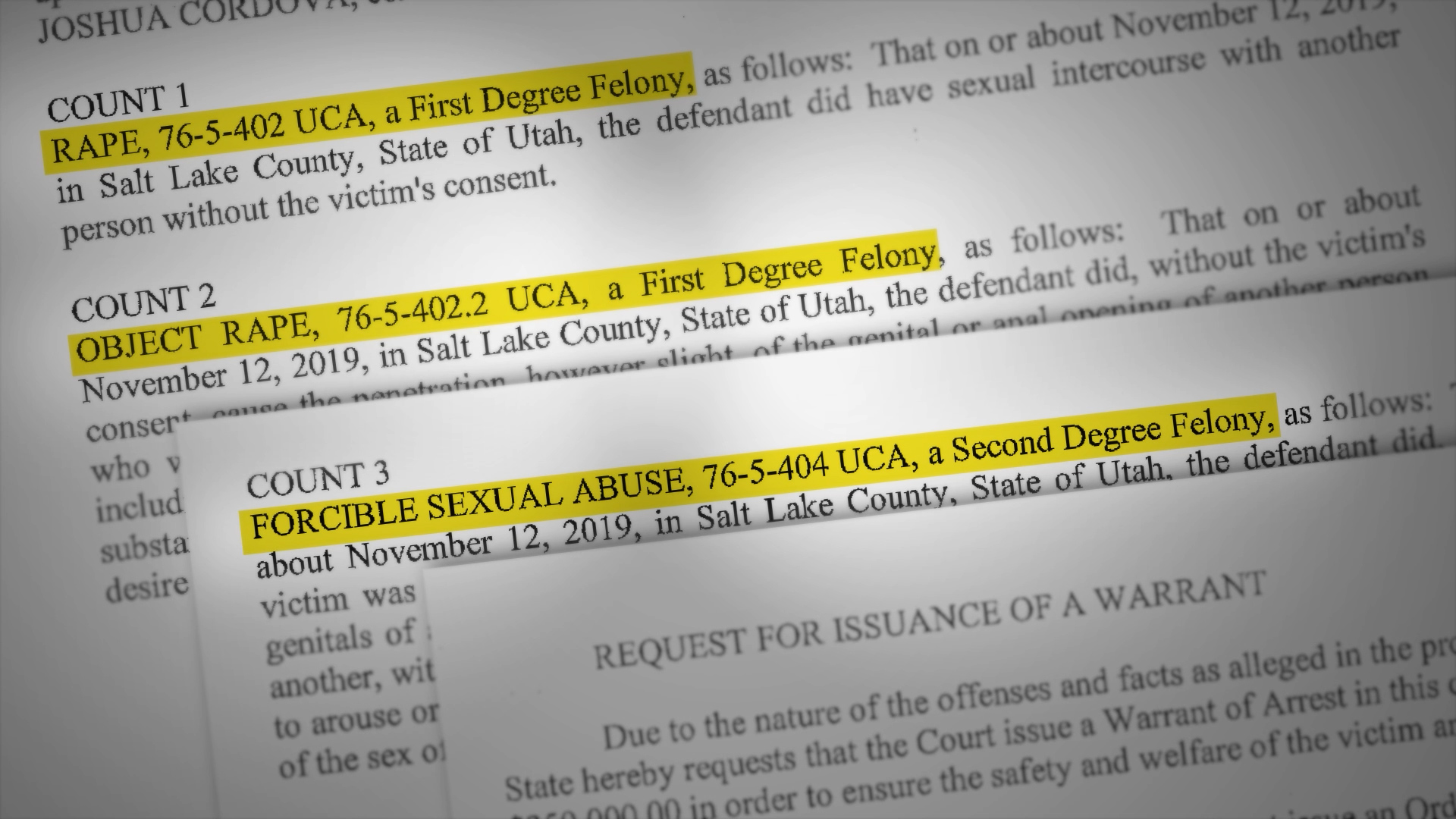

Flint notes reports of sexual violence continue to surface. Her lawsuit notes that in a separate case, a different USU football player was formally charged with rape in April in the wake of the DOJ report. Ismael Vaifo’ou has pleaded not guilty in Logan’s 1st District Court.

The DOJ began its review in 2017 after students alleged the university failed to respond to several reports of sexual assaults. The probe followed a series of criminal charges for former USU football star Torrey Green, who was convicted of raping several women in 2019. Another student alleged that a one-time fraternity member at USU was accused of assaulting five women before he raped her.

Have you experienced something you think just isn’t right? The KSL Investigators want to help. Submit your tip at investigates@ksl.com or 385-707-6153 so we can get working for you.