Punched. Kicked. Spit on. Assaults on the rise against Utah health care workers

Feb 3, 2022, 10:03 PM | Updated: Jun 19, 2022, 9:57 pm

SALT LAKE CITY — Health care workers – touted as the heroes of the pandemic – have not just taken a mental beating, but a physical one.

How often it happens, and the intensity of the abuse, may shock you.

In court documents, KSL Investigators found chilling narrations. One reads, a patient “punched the nurse in the side of the head.” Another, “kicked the worker in the face three times.” One harrowing report detailed a patient assaulted a nurse “by punching her repeatedly in the head, kicking her in the stomach… and literally ripped her hair out.”

During an incident reported at a Provo hospital in December 2020, a patient punched another patient “without provocation,” and then beat the nurses who tried to stop the attack, “punching… in the head/face with a closed fist three times.”

A security guard who intervened was struck “in his head/face and body in excess of 12 times before other staff were able to get in the room and restrain” the patient.

Both nurses and the security guard were treated for their injuries in the emergency department.

“It’s not part of the job”

Violent episodes against medical staff aren’t new. But these attacks are happening with more frequency, as KSL Investigators discovered after months of asking Utah’s largest healthcare organizations for data.

Numbers compiled for KSL by the Utah Hospital Association show 21,813 incidences of verbal and physical abuse perpetrated on healthcare workers between 2019 and 2021 at Utah’s four largest health care companies.

Numbers released by the Utah Hospital Association (UHA) for KSL TV show 21,813 incidences of verbal and physical abuse perpetrated on healthcare workers between 2019 and 2021.

These cases increased 13% between 2019 and 2021.

The data was collected by the four major healthcare groups in Utah: Intermountain Healthcare, MountainStar Healthcare, Steward Health Care and University of Utah Health. It represents cases from across all their hospitals, urgent care centers, freestanding emergency departments and clinics within the state.

KSL Investigators heard from dozens of health care workers with their own abusive experiences: being screamed at, swatted, punched, even stabbed. All said while abuse existed before COVID-19, the pandemic seemed to expose and exacerbate the problem. None of these workers were willing to talk with us on camera about their experiences, citing fears of being fired from their job for speaking out.

All except Stephanie Sphar, who worked as a nurse for 18 years. Sphar, who now works in a skilled nursing facility, spent more than a decade at multiple Wasatch Front hospitals, including emergency departments.

Stephanie Sphar has been a nurse for 18 years. She spoke about her experience of verbal and physical assaults with KSL’s Mike Headrick. (Ken Fall/KSL TV)

Sphar said abuse on the job is common.

“I would say to me, it happens about once a week,” she said. “It’s mainly verbal. I’ve had to hang up on patients’ families before and just said, ‘I’m sorry, when you can talk to me like a normal human being, call back.’”

Based on what’s she has heard from her friends still working in the hospitals, Sphar said it’s happening more often. “There is one healthcare worker in every hospital, either verbally or physically assaulted in a 24-hour period, if not more,” Sphar estimated.

Sphar said she was physically assaulted once, a few years ago while working at an Ogden hospital, when she tried to help a colleague who was attacked.

“I ran down and saw my friend, a fellow nurse, being attacked by a patient’s wife, because as I found out later, his medications were late,” Sphar recalled. “So, I put my arms around (the nurse) and I pulled her out of the room, and I just saw this woman coming at me.”

Sphar said the woman charged them, causing them all to fall. The nurse was scratched and bruised. Sphar said she hurt her knee in the fall.

Security removed the woman from the hospital, but Sphar said no charges were ever filed in the incident. “There was nothing.”

Little prosecution for abusers

Trying to determine the frequency of abuse against healthcare workers proved difficult.

It wasn’t until KSL asked for the data that UHA began collecting it from the major hospital groups. There is little in the way of reporting requirements.

The Utah Labor Commission does collect data for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on nonfatal incidences of violence involving days away from work.

The data shows number of cases to be about the same year over year, with just as many cases reported in 2011 (40) as in 2020 (40).

Utah does have a law designed to protect hospital workers who are assaulted or threatened while trying to provide medical help to a patient.

KSL Investigators dug through court records and found prosecution under this law is rare.

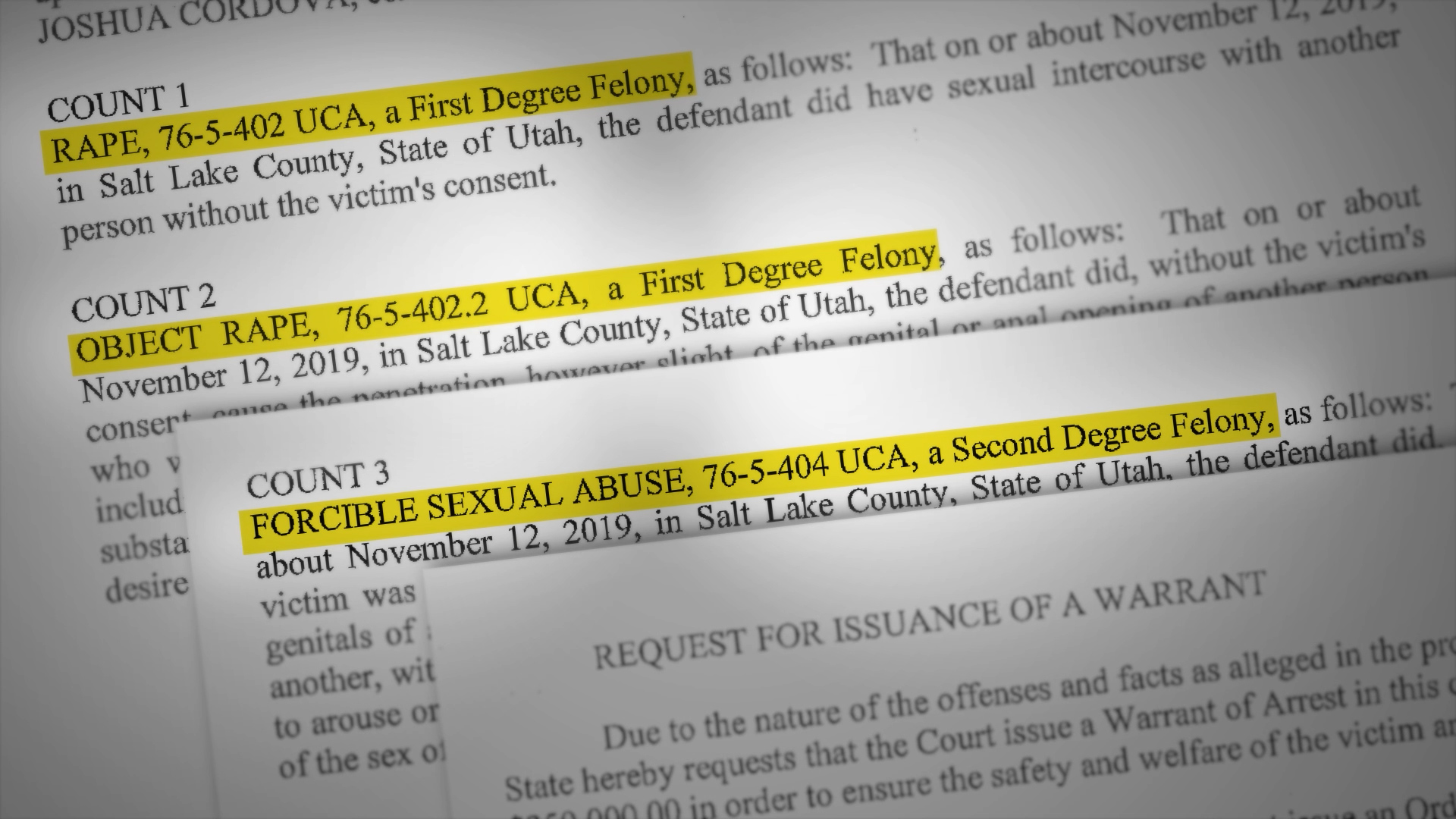

Between March 3, 2020, and Nov. 15, 2021, just 142 criminal cases were filed statewide under the health care worker protection law.

That number represented fewer than 1% of the verbal and physical assaults reported by UHA.

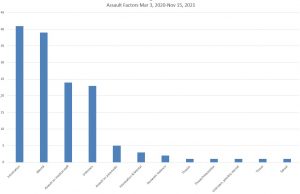

KSL’s analysis of probable cause statements for the 142 cases of hospital assault prosecuted during the pandemic found intoxication was a factor in 41 cases. Thirty-nine cases cited an individual experiencing a mental crisis.

Analysis of probable cause statements for those 142 cases prosecuted during the pandemic shows the most common factor in assaults is intoxication, either by drugs or alcohol. It factored into 41 cases, or 29%.

Thirty-nine cases cited an individual experiencing a mental crisis.

Not all cases listed the location of the assaults. But of the 121 that did, KSL found 36 cases prosecuted happened in Intermountain Healthcare facilities.

Steward had 27 prosecuted cases. MountainStar saw 19 prosecutions of violent patients. University of Utah Hospital saw three prosecutions in that time frame.

Of individual hospitals, Lakeview Hospital in Bountiful was named in 10 prosecutions, followed by Jordan Valley West (nine), Davis Hospital (nine), Utah Valley Hospital (eight) and Intermountain Medical Center (five).

There were difficulties in obtaining a complete data set, as 23 court cases and probable cause statements did not list the narrative of the attack or the location of the attack.

Utah’s law also protects EMS workers, which accounted for 22 of the prosecuted cases in 2020-2021.

Abuse is underreported

Dr. Liz Close, executive director of the Utah Nurses Association, said the actual number of abusive incidences is likely higher.

“Frequently, if they are hit or harmed, they don’t report it,” said Close. “Nurses are extremely empathetic, and do not have the ability to simply abandon their patients.”

Her explanation was one we heard from many nurses: Patients visiting the hospital are often having a really bad day, and healthcare professionals don’t want to make it worse. She said the pandemic changed a lot, with medical professionals on the receiving end of abuse thanks to a mix of misinformation, politics, and growing strains on mental health.

“When we started out, nurses were heroes in the pandemic,” Close explained. “Now they have become pariahs because we have to tell people they’ve got COVID, and they don’t think there’s such a thing. We have to prevent people from coming in and out of the rooms to keep control on the spread of the disease, so we kind of come out being the bad guys.”

“Family members, patients, other friends and stuff are frustrated and angry, because they think they’ve been lied to,” she continued. “When you get to that level of sense of loss of control, the closest people you take it out on are nurses because they’re at the bedside. The problem, she said, is there’s no consistent reporting mechanism to track abusive events.

“I can’t tell you numbers because I don’t know a central location, other than the Bureau of Labor, that collects any kind of information,” said Close. “With the reporting not being consistent, that’s a problem.”

UHA admitted in their report to KSL TV that “each health care system collected their incident information in different ways. UHA has tried to represent the reported data as accurately as possible, taking these differences into consideration when preparing this report.”

Challenges to curbing violence

Dave Gessel, executive vice president of UHA, said hospitals all have protocols in escalating violent situations that may result in prosecution.

“They train their caregivers to de-escalate and not escalate,” said Gessel. “So, there’s that front-end where that happens successfully in a lot of cases.”

UHA “conservatively” estimated that Utah hospitals saw more than two million emergency department encounters, “more than 775,000 inpatient visits, and more than five million outpatient visits/encounters in Utah over the 2019-2021 period.”

These estimates would indicate reported abusive incidences accounted for 0.28% of all medical visits in 2019 through 2021.

“If it does turn violent, or continues on, there are policies where virtually every hospital has security that’s then called,” said Gessel. “If it escalates further, of course the police are called, and then that process takes on its own process. We don’t control what the police will do or what the prosecutors will do.”

A bill sponsored by Rep. Robert Spendlove, R-Salt Lake City, would provide more opportunities for prosecution. HB32, introduced this session, would expand protections.

“Currently, if someone were to attack a health care worker in the emergency room, it’s a class A misdemeanor that can result in up to a year in jail,” said Spendlove. “But it’s just for the emergency room. What this bill will do is it will take that enhanced penalty for attacking a healthcare worker and expand it to cover the entire hospital and cover physicians’ offices.”

Spendlove said anecdotes he’s heard from healthcare workers indicated the violence is tied to symptoms of the pandemic so his bill would add a sunset date on the penalties of Jan. 1, 2027.

As of Feb. 3, the bill had passed the Utah House of Representatives 56-16-3 and has been sent to the Utah Senate for consideration.

Close said violence in hospitals isn’t a new problem and would like to see more done on a federal level. The Utah Nurses Association supported HR1195, the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act.

The bill would task the U.S. Department of Labor to create a temporary, uniform requirement where certain health care facilities must “develop and implement a comprehensive workplace violence prevention plan,” including how to report violent incidents.

The temporary rule would need to be in place within a year after passage, with a final rule to be researched and put in place within 42 months after passage.

The bill passed the U.S. House of Representatives in April 2021 with bipartisan support but has had no action in the U.S. Senate.

None of Utah’s congressional delegation voted for the bill.

KSL reached out to all four Utah congressmen to find out why. Reps. Burgess Owens and Blake Moore did not respond to our request. Two sent statements.

Rep. Chris Stewart’s read in part, “At the time of this vote, OSHA was in the process of drafting a workplace violence rule that would have given these frontline workers the protections they deserve. This drafting process included collecting and analyzing important stakeholder input to ensure the most effective, protective, and feasible standard for workers. I voted against H.R. 1195 because it was a rushed, federal standard that undermined and disrupted this ongoing, evidence-based process.”

Rep. John Curtis said he voted no because, “This bill requires a hasty and flawed regulation that ignores expert and practical input and imposes overly prescriptive mandates that will eliminate higher quality, more protective, and practical solutions.”

Gessel agreed that more federal regulation would be unhelpful in curbing hospital violence. “Hospitals are very complex, large enterprises that already have literally tens of thousands of pages of regulations and things they have to follow,” he explained. “A lot of times hospitals just feel like we can’t even hardly do what we’re requested to do now.”

Gessel said there are conditions under which he’d be more open to centralized reporting.

“If what we’re trying to pass in the state doesn’t make a difference, if society doesn’t get a little better, if this continues to escalate, then I think, sure, we’d want to have that,” he said.

A plea from health care workers

Gessel said hospitals have taken steps to protect workers.

“Hospitals have had to and do have serious security that we didn’t have 20 years ago,” he said. Many facilities have specific emergency response teams and procedures to handle out-of-control patients and visitors.

Ultimately, Gessel told us he hopes state legislation sends a message to potential abusers.

“This should be a place of healing and health and help us do that by being on your normal, civilized behavior.”

Sphar added nurses and healthcare workers continue to deal daily with staffing shortages, COVID infection, and a heated social environment.

“Be patient with us,” she pleaded. “We’re doing the best we can with what we have.”

Have you experienced something you think just isn’t right? The KSL Investigators want to help. Submit your tip at investigates@ksl.com or 385-707-6153 so we can get working for you.