Last chance for a life out of max: How some Utah death penalty inmates made it to medium security

Mar 13, 2022, 11:19 PM | Updated: Jun 19, 2022, 9:25 pm

DRAPER, Utah – For decades, people sentenced to die by Utah’s courts have served their time in solitary confinement at the Utah State Prison.

That changed on March 28, 2019, when the Utah Department of Corrections implemented an untested new approach: transferring the majority of those sentenced to death out of the maximum-security cell block they’d long occupied.

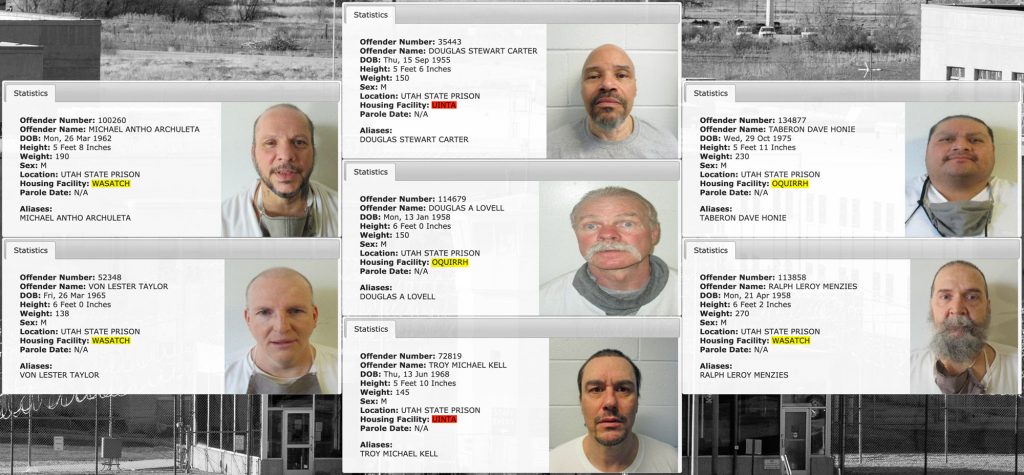

As a result, only two of the seven men sentenced to death in Utah today remain in maximum security. The other five are living in more comfortable, less secure areas of the prison while awaiting execution.

Seven men have been sentenced to die in Utah. This photo shows the location where each is housed at the Utah State Prison as of June 2021. Inmate photos courtesy Utah Department of Corrections. (Dave Cawley, KSL Podcasts)

The move did not amount to abolishing the death penalty in Utah — capital punishment policy is set by the Legislature — but it ended the longstanding practice of housing inmates who are sentenced to death in a single unit, or “death row.”

The department made the change without notifying the public.

Inmate classification

The department’s own inmate classification policy has for decades stated inmates sentenced to death were to be automatically assigned custody level 1. That maximum-security designation was reserved for “inmates that pose the highest threat to institutional security and the safety of staff, other inmates and/or self.”

That inmate classification policy also said death penalty inmates were not eligible to have their custody level reviewed or changed, as all other inmates were, unless their convictions were overturned, or sentences commuted.

By moving death penalty inmates out of maximum security in 2019, prison staff appeared to be acting in violation of their own inmate classification policy.

Corrections leaders did not announce the moves publicly or provide any rationale for them. Public-facing documents available through the Department’s own website continued to describe life on death row as a maximum-security situation as recently as March of 2021, well after the moves were complete.

Families of the victims in Utah’s seven current death penalty cases were not notified of any change of status for the men convicted of killing their loved ones. Some only learned of those changes when contacted by KSL last year.

The ‘Last Chance’ policy

KSL first became aware of the behind-the-scenes change in housing of death penalty inmates while conducting research for the second season of its investigative podcast series, COLD. Podcast host Dave Cawley asked Corrections Executive Director Brian Nielson about the move in a June 2021 interview.

Nielson acknowledged people sentenced to death had traditionally been housed in “very restrictive” settings, without the option to do anything else. He attributed the change in 2019 to an old, previously undisclosed policy.

“In 2005, there was a policy enacted called Last Chance policy that gave a pathway for [death penalty inmates], if they could earn it, on how to be in a less-restrictive housing setting. We’ve had a couple make it that far, but it’s taken 13, 14 years to get there.”

KSL subsequently filed an open records request for a copy of the “Last Chance” policy. Corrections at first denied the request, stating the policy was “protected” under the Utah Government Records Access and Management Act, but reversed course after KSL appealed the denial.

Utah DOC Last Chance Program Policy by LarryDCurtis on Scribd

The version of the Last Chance policy the department provided had been in effect during 2019, as well as in 2021 when Nielson had referenced it during his interview. Corrections blacked out a portion of the document labeled “inmate housing,” but left clear another portion that reads “the Utah Department of Corrections Inmate Classification policy does not allow inmates sentenced to death to advance beyond a classification Level One, maximum security.”

Privileges in prison

The Last Chance program, as conceived, was meant to improve the “personal growth and social functioning” of inmates who were housed on death row, to provide them opportunities for public service and to offer “meaningful programming to demonstrate [their] positive behavior.” It did not list moving death penalty inmates out of maximum security among its objectives.

Instead, inmates taking part in the Last Chance program were offered a narrow set of additional privileges not typically afforded them due to their Level 1 classifications. Those included extra time out of their cell each day, or increased access to the prison’s commissary, mail, or phones.

Last Chance program participants were able to earn those privileges by demonstrating good behavior. Eligibility required they take part in educational and therapeutic programs and control their day-to-day behavior.

Excluded from Last Chance were any inmates who’d committed crimes or serious disciplinary infractions while incarcerated, or those who’d exhibited aggressive, abusive, or threatening behavior. Troy Michael Kell — who’d murdered another inmate while already in prison — was for instance not eligible for the Last Chance program.

Vera Institute of Justice

In 2017, the Utah Department of Corrections began a partnership with a New York-based non-profit organization called The Vera Institute of Justice. Vera had received federal grant money to study the use of solitary confinement at several prison systems across the country, including in Utah.

Corrections opened its records to Vera. It allowed the organization to examine its policies — even those the public was prohibited from seeing like Last Chance — along with nearly two years of demographic data. Vera representatives toured the state’s two prisons, where they conducted focus groups with staff and inmates alike.

Emails between Vera staff and corrections leaders obtained by KSL through an open records request show Vera delivered a set of preliminary observations and recommendations to the department in May of 2017. By that point, the department had already started making proactive changes to its policies regarding inmate classification and housing.

Vera’s final report, dated January of 2020, included Vera’s determination that inmates serving death sentences “do not warrant automatic, preemptive segregation” because “there is no indication that they commit more infractions or engage in violence more than any other subpopulations.”

Changing ‘Last Chance’

A correctional officer named Richard Hayes sent a letter to his boss, deputy prison warden Kent DeMill, in January of 2018. KSL obtained a copy of the Hayes letter through an open records request.

U1 Level 3 Revised Redacted by LarryDCurtis on Scribd

Hayes was then serving as captain over Uinta 1. He proposed a significant change to the 2005 Last Chance program. Instead of simply rewarding death row inmates with additional privileges, Hayes suggested modifying the program to allow those inmates to have their classifications changed to Level 3.

Level 3 inmates live primarily in medium-security housing units and comprise the bulk of the prison’s general population. Hayes’ proposal was to allow death penalty inmates a much greater privilege than they’d previously been offered: an ability to leave maximum security for good.

The end goal, Hayes wrote, “would be to transition [Last Chance Death Row] inmates out to general population after a successful program and eliminate the [Last Chance Death Row] program all together.”

It was, in effect, a proposal to dismantle Utah’s death row.

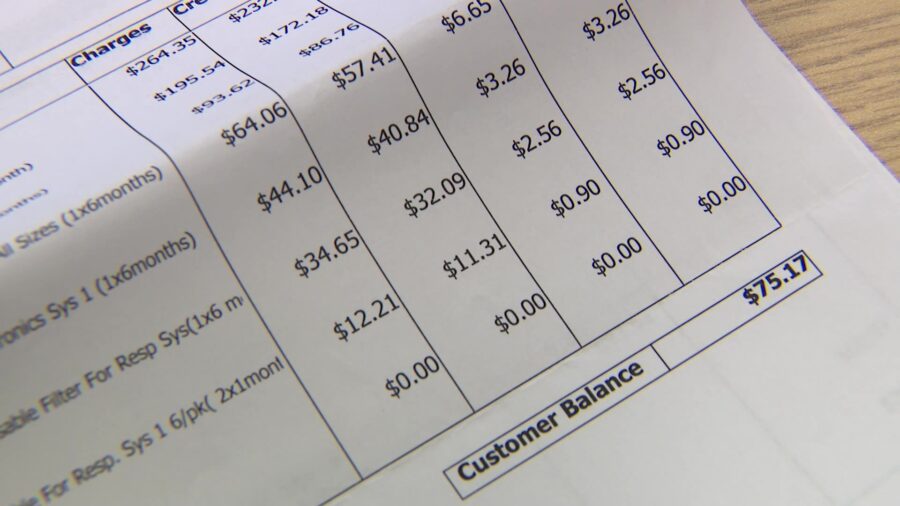

Utah’s Legislature was at that same time preparing to debate a death penalty repeal bill. Just months earlier, Utah’s Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice had issued a working group report examining the costs and public opinions surrounding the death penalty. The report estimated each death sentence delivered in the state cost taxpayers roughly $1.7 million more than if the sentence had instead been life without parole.

Utahns had traditionally shown strong support for capital punishment, the report said, but the most ardent proponents were people who were “male, older and more conservative.” The report concluded death penalty support in Utah was likely “declining over previous highs” in light of national trends.

One of the CCJJ working group members responsible for preparing that report was Jerry Pope, director of the Division of Institutional Operations at the Department of Corrections. Pope was directly over Richard Hayes in the department’s organizational structure.

The Hayes letter proposed phasing in the change to the Last Chance program in three stages, over a period of 360 days. Phase one would involve allowing the Last Chance inmates out of their maximum-security cells together for expanded recreation time. This would effectively change the death row block of Uinta 1 — the prison’s super-max building — into an “open section.”

During phase two, Last Chance inmates would gain additional freedom of movement around Uinta 1. They would also get the opportunity to join in mental health counseling sessions typically reserved for inmates who are serving life sentences.

Last Chance inmates who made it to phase three would begin wearing white, instead of orange, in preparation for their final transfer to medium-security housing units among the general prison population.

A few months following the Hayes letter, in April of 2018, the Department of Corrections updated the Last Chance policy. But that revision did not reflect the proposals put forward by Hayes and the Uinta 1 staff.

A January 15, 2019 update to the prison’s inmate classification policy likewise retained that document’s mandate that death row inmates be classified as Level 1 offenders, who were only to be housed in maximum security.

Yet, internal department emails obtained by KSL reveal on March 28, 2019, Hayes implemented phase one of the new Last Chance plan, contrary to corrections’ published policies.

A lot of ideas from the Last Chance inmates

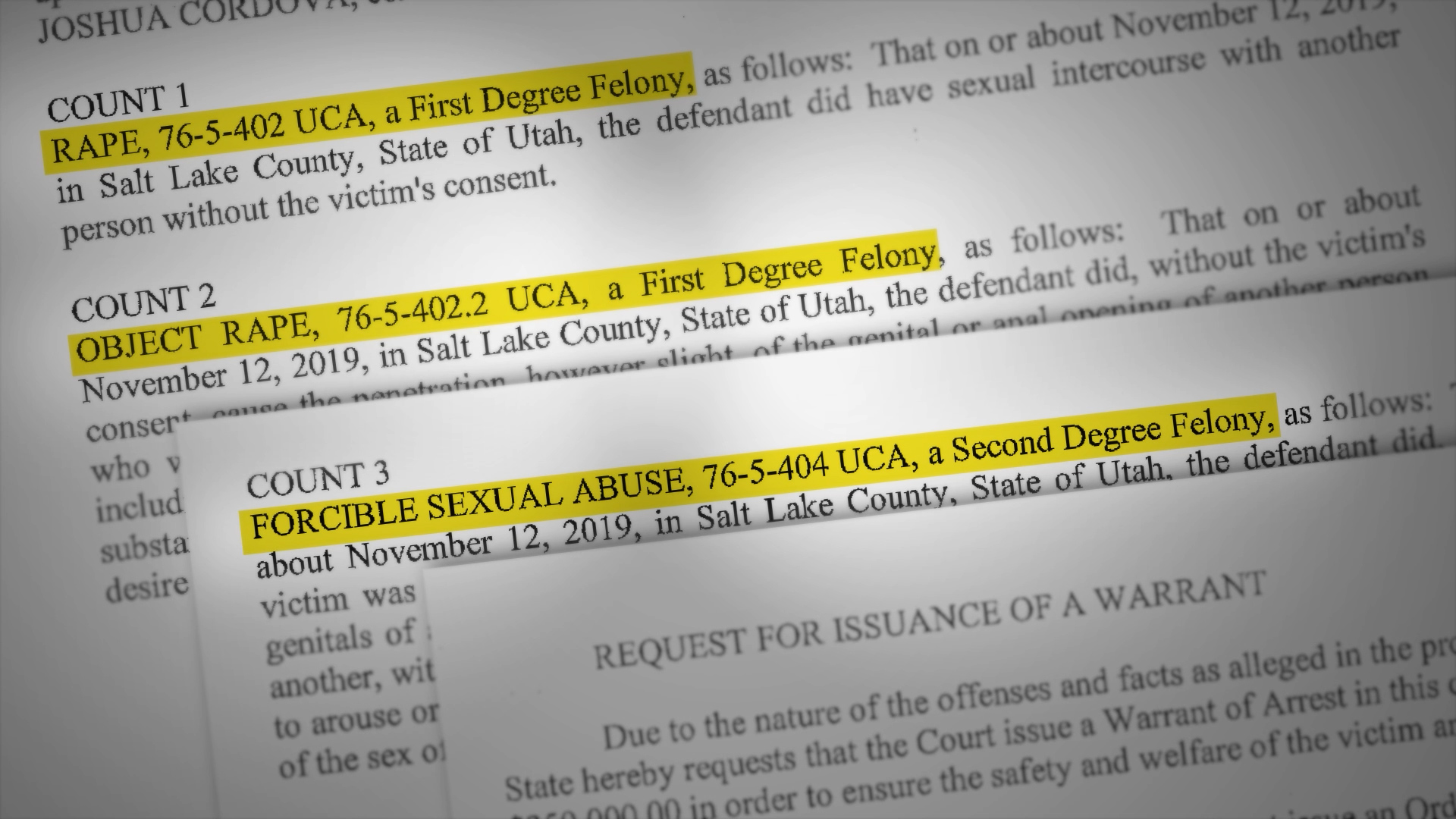

Days later, death row inmate Douglas Lovell sent a series of letters to multiple female staff members at KSL TV and KSL NewsRadio. Lovell’s letters included a brief, handwritten description about how he’d felt depressed and suicidal upon arriving at the Utah State Prison in 1986. He included a pamphlet that promoted suicide prevention resources, which he’d produced with the assistance of a Utah-based non-profit organization called Rising Star Outreach.

This unsolicited burst of mailings was out of character for Lovell, who’d declined requests for media interviews for more than 25 years. Each letter was almost identical, raising the possibility they could’ve been written to satisfy the Last Chance program’s community service requirement.

Richard Hayes, the captain over Uinta 1, warned his staff in a June 17, 2019 email they would receive “a lot of ideas coming from the [Last Chance Death Row] inmates” about how things should go as they moved forward. Hayes advised his officers phase two was soon approaching and they were expected to stick to the plan, no exceptions.

Other internal department emails obtained by KSL revealed the rushed implementation of the new Last Chance policy caught even other members of the corrections hierarchy by surprise.

In late August of 2019, department public information officer Kaitlin Felsted sent an email with the subject line “Last Chance Program Questions” to Victor Kernsey, Corrections’ Director of Institutional Programming.

The contents of Felsted’s email were redacted in the copy obtained by KSL. However, metadata suggests Felsted forwarded the same question to Jeremy Sharp, the department’s Director of Prison Operations a week later. Sharp, in turn, forwarded Felsted’s message to Draper prison warden Larry Benzon.

Benzon’s response to Sharp, also largely redacted, described Last Chance as a “new program” which was at that time approaching its third and final phase.

Sharp replied to Felsted, telling her Last Chance was a “draft policy” and a “housing strategy we are utilizing as part of adjusting our use of segregation.”

Another email chain showed the “draft” version of the Last Chance policy was not submitted for final approval with the executive director of the Department of Corrections until May of 2020.

By that time, the issue was effectively moot. The new, draft version of Last Chance had already been fully implemented.

Death row dismantled

When Utah Department of Corrections Executive Director Brian Nielson arrived at KSL Broadcast House for his June 2021 interview, he was accompanied by public information officer Kaitlin Felsted.

Felsted was standing nearby when Nielson attributed the move of the death penalty inmates out of maximum security to the 2005 version of the Last Chance policy. She did not correct Nielson’s statement during or after the interview, even though she had herself been told less than two years earlier the policy was “new” and implemented in a “draft” version.

Nielson did not disclose that the 2018 rewrite of the Last Chance policy was part of a larger shift away from the use of segregation by the department or attribute the influence of The Vera Institute of Justice on that strategy.

When KSL then sought a copy of the Last Chance policy from the department, Corrections Deputy Director James Hudspeth responded it was “in the process of being significantly rewritten.” In a letter, Hudspeth wrote that review had started in 2020 and the draft version was “likely to soon be altered substantially.”

Hudspeth, like Nielson, failed to disclose the “draft” version of the Last Chance policy first proposed in 2018 had already been put into practice. Death row — a single place where inmates sentenced to die are housed together — was no more at the Utah State Prison.

RELATED LINKS:

KSL Investigators Explore Change in Utah’s Death Row

Utah allowed rival gangs to mingle in prison; families say violence followed