Utah placed limits on police use of spy tech; Do they go far enough?

Jun 30, 2022, 10:29 PM | Updated: Jul 1, 2022, 10:47 am

For months, the KSL Investigators have been asking questions about spy technology law enforcement uses but doesn’t want to talk about. What exactly does the high-tech tool do, and what happens to your information if it gets caught up in a digital dragnet?

SALT LAKE CITY – A week after University of Utah football player Aaron Lowe was shot and killed outside a Salt Lake party last September, Salt Lake City police were still searching for their homicide suspect and still coming up short.

They turned to a powerful, secretive backup tool: spy tech that picks up cell signals, allowing them to pinpoint a person’s real-time location and potentially eavesdrop on calls and texts.

It’s called a cell site simulator – often referred to by the brand name StingRay. The portable device mimics a cell tower, forcing phones to connect and share data. Hours after a judge signed a warrant allowing police to fire up the tool, authorities found and arrested Buk Mawat Buk, court records show.

They won’t say how they found Buk in Draper last October, or even confirm they used the tool. But KSL Investigators found traces of their efforts to use the surveillance method in unsealed search warrants.

The sophisticated devices can cast a wide net, sweeping up cell phone chatter and data from anyone nearby, not just the person police are looking for. But whether they can see you scroll, type and tap in apps is still a secret – and that’s by design. In order to make use of it, some departments have signed nondisclosure agreements managed by the FBI.

Privacy advocates continue to raise alarms about how law enforcers use the stealth-technology – and what happens to any unrelated information from other phones caught in the dragnet.

Nate Wessler, a deputy project director with the American Civil Liberties Union, says there’s no way to know if a StingRay has gathered your information. (KSL TV)

“Police are not allowed to knock down every door in a neighborhood, looking for a particular suspect,” Nate Wessler with the American Civil Liberties Union said. “This technology is the digital equivalent of that in important ways.”

But no glass shatters and no wood splinters when police intrude on a person’s digital privacy, so it’s impossible to know if it’s happened to you, said Wessler, a deputy project director focused on speech, privacy, and technology at the ACLU.

Privacy v. public safety

Utah was one of the first states to rein in police access to cellphone data with a 2014 law. The change required them to obtain warrants first, like they would to enter a home, and notify the target of the warrant after the fact. The state went a step further than others at the time, barring police from using information or data from anyone not named in the warrant and requiring them to delete the unrelated data.

Critics say it’s still too easy for authorities to use the tool in secret without first obtaining permission from a judge. But law enforcers in Utah insist they’re playing by the rules in their investigations.

If they didn’t, the consequences could be enormous, Nick Chournos, Utah’s supervisory deputy U.S. Marshal said.

“We don’t want to sidestep something and do things the wrong way. That gives lawmakers the ammo they need to say, ‘You know what? They’re abusing this authority,’ and take it from us,” Chournos said. “If we’re not approved to do something, then we don’t do it. We don’t use it.”

Nick Chournos, Utah’s supervisory deputy U.S. Marshal, talks about working with Utah’s Violent Fugitive Apprehension Strike Team, or VFAST, in May 2022. (Ken Fall/KSL TV)

The devices can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars – too pricey for most local police departments.

Instead, Utah agencies sometimes work with federal law enforcers like the Marshals. That’s the approach Salt Lake City police took to find Buk in October, court records show.

KSL Investigators surveyed more than 40 law enforcement agencies in Utah about the tools. Of those that responded, sheriffs’ offices in Utah County and Davis County confirmed the device has played a role in their investigations. We asked every department for copies of their policies governing the use of the technology. Just one – Salt Lake City police – sent us a document, but it doesn’t mention cell site simulators or how to handle data from other parties.

Salt Lake City police spokesman Brent Weisberg said the department uses this sort of technology in rare cases and in collaboration with an outside agency, but only with proper approval.

While they won’t talk about the details, the KSL investigators found more than a dozen search warrants requested in the last two years by Marshals stepping in to help local teams track down Utahns flying under the radar.

They include a variety of cases, most of a serious nature, like an alleged heroin trafficker who disappeared in 2020. But one pertained to a woman with no violent offenses, accused of shoplifting and trying to get away from police, according to court records.

Wessler said it’s common for police across the country to break out the tools even in low-level cases. In Maryland, Annapolis police obtained a court order to use the equipment to find whoever stole chicken wings and sub sandwiches from a delivery driver, Capital News Service reported.

Salt Lake City police noted the investigative technique recently helped them arrest a homicide suspect. And the Davis County Sheriff’s office acknowledged the technology has helped them solve sex crimes, find missing children and capture those wanted in connection with violent crimes. But neither agency went into specifics.

Law enforcers say talking about the technology could backfire.

In Salt Lake City, a spokeswoman for the FBI said the agency respects privacy and civil liberties but declined to talk about the device. Doing so, she said, “would make public sensitive law enforcement tools and techniques, that could facilitate terrorists, kidnappers, fugitives, drug smugglers, and other criminals to determine our capabilities and limitations in this area and may enable them to evade detection.”

Chournos agreed. He said his team isn’t interested in bulk surveillance.

“We’re trying to hunt down fugitives. That’s the person we’re looking for and the information we want,” he said. “And that’s the information we retain.”

But there are other benefits to the secrecy, said Wessler, whose organization is suing the FBI to find any current confidentiality agreements tied to the devices.

“The fewer people that know what police are doing,” he told KSL Investigators, “the less pushback there’s going to be when police are getting close to the line of people’s constitutional rights.”

Law’s limits

Utahns may shrug off those concerns if they feel they have nothing to hide, but there are still risks, said Connor Boyack, president of the libertarian-leaning Libertas Institute.

“Everyone has something to hide,” said Boyack, who helped craft the 2014 Utah law. “It may not be illegal, but there are things that you don’t want someone snooping around and looking into your personal life. Do we really think that some underpaid bureaucrat at some government agency should have unfettered ability to scan the contents of your cell phone whenever he wants?”

Connor Boyack, president of the libertarian-leaning Libertas Institute, helped craft a 2014 Utah law placing limits on police use of cell site simulators. (Josh Szymanik/KSL-TV)

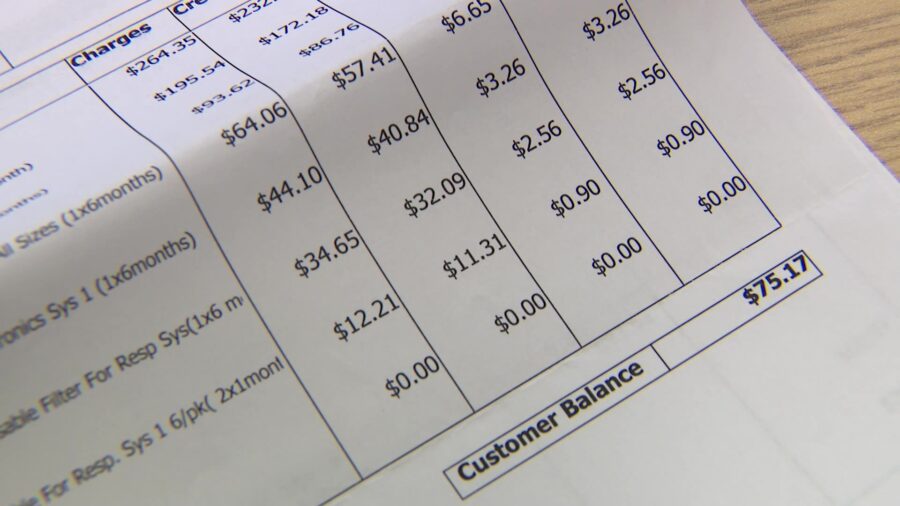

If police scoop up data from someone else – not the person named in a warrant – Utah law requires police to destroy it “as soon as reasonably possible.” But there’s no penalty spelled out for police departments who hang onto the information or sidestep the warrant requirement.

“Despite passing that law, we still just have to trust that it’s being enforced and adequately followed,” Boyack said.

Any public mention of the technology is rare.

It happened in a Utah court case earlier this year, however, in a hearing for a former Salt Lake City employee accused of telling an alleged human trafficker about undercover investigations. The employee warned the pimp about a cell site simulator scanning downtown Salt Lake City, according to prosecutor Kaytlin Beckett with the Utah Attorney General’s Office.

“He very clearly says, ‘StingRay’s being used in this area, can pick up all cell phone chatter, all cell phone information within a one-mile radius,’ ” Beckett said in the March 10 hearing. “That’s what a StingRay does.”

Defense attorneys are sometimes suspicious the device has been used but can’t track down the evidence to prove it, said Greg Ferbrache, the defense attorney representing the onetime city staffer, Patrick Driscoll.

“We end up punching into the air,” Ferbrache said. He argued in court there’s no evidence any StingRay was actually being used in the area at the time and told KSL the state should hand over any warrant tied to that investigation.

Utah requires state and local police to get a warrant in most cases, along with anyone acting on their behalf. The U.S. Department of Justice policy directs federal officers to do so, too, but it does allow exceptions, like when officers are trying to prevent serious injury or death, or in “the hot pursuit of a fleeing felon.”

Rep. Ryan Wilcox, R- Ogden, who sponsored the 2014 measure, said it put Utah on the “leading edge” in protections for data privacy, and police “understand the goals that we have here and have been very helpful along the way.”

But Wilcox recalls one law enforcement officer telling him that a trove of data from one search helped them catch others carrying out crimes.

“Because you also violated another 2,000 people’s privacy at the time,” he recalled thinking.

Boyack, with the Libertas Institute, said if police are using the tool more often, the state should require them to register the devices and send lawmakers reports on when and how they’re using them.

“We should have more accountability and transparency,” he said.

Emiley Morgan contributed research to this story.

This story from the KSL Investigators is one in a series exploring the state of data privacy and policing in Utah. Have you experienced something you think just isn’t right? Submit your tip at investigates@ksl.com or 385-707-6153.