Smelly, potentially toxic dumping in Beaver County has neighbors concerned

Aug 31, 2022, 10:54 PM | Updated: Sep 1, 2022, 12:21 am

BEAVER COUNTY, Utah – There is something that stinks in Beaver County and people are fed up.

“It’s not this, ‘Oh, I get a glass of milk out of the fridge and it’s bad kind of smell to it,’” Dustin Cooney said. “This is just real rotten.”

For 40 years, Cooney and his family have lived about four miles west of Interstate 15 in the community of Greenville. Across from the Cooney’s property is a hill, known by residents as Whey Hill.

“Everybody in town calls it that,” Cooney said.

For decades, the hill was a dumping site for whey, a liquid derived from cheese production which is often used as fertilizer.

Beaver County resident Dustin Cooney said he took this photo in July after watching 12 trucks dump milk on Whey Hill. (Courtesy Dustin Cooney)

But for months, Cooney has been documenting trucks dumping large quantities of milk on the hill.

“Full tankers coming out here,” Cooney said. “They come out here from 5:00 in the morning until noon.”

He says at times it looks like foamy white river. And he’s concerned about where the milk is going.

KSL TV’s drone flew over the property and captured images of a large man-made basin full of a dark red, rotting milk covered in algal blooms.

“You can see the milk; that’s milk decomposing right there,” Cooney said as he showed KSL TV’s Shara Park the dump site from Pass Road. “How is this legal in this day and age?”

Standing on the edge of Cooney’s property, there is a putrid smell coming from the hill. But Cooney and his neighbors say the smell is the least of their concerns. What they’re really worried about is their ground water.

“My concern is that if they don’t do something to remediate this, how long before it gets into the water aquifer and how long will it travel before it gets to us?” Russell Meadows, who lives about two miles from Whey Hill said. “Something’s got to be done.”

According to Beaver County property records, the 40-acre parcel of land is owned by Dairy Farmers of America, the company that owns the popular Creamery just off I-15.

Until 2018, the company held a custom blended fertilizer license from the Utah Department of Agriculture. That license allowed it to incorporate dairy processing wastewater or whey into the land. But then its operation changed.

“At which point permits were evaluated and it was determined that because they were not selling fertilizer from their place that they did not need that particular permit,” Bailee Woolstenhulme, a spokesperson for the Utah Department of Agriculture said.

Woolstenhulme said when Dairy Farmers of America changed its operation from dumping whey and incorporating it into the ground to dumping milk and letting it pool, they should have applied for a groundwater discharge permit from Utah’s Division of Water Quality.

“If they were making any operations changes, they probably should have checked with our department or another department to see if they needed to change or get a different permit,” Woolstenhulme said. “I think it was probably just a misunderstanding, unknown knowledge of what needed to be done in this circumstance.”

According to the Utah Division of Water Quality, Dairy Farmers of America never applied for the groundwater discharge permit, and it currently don’t have one.

“No, they don’t,” John Mackey, Director of Utah’s Division of Water Quality said. “We’ve asked the industry to provide some information about the materials that they’re disposing.”

An investigation by the Division of Water Quality into the dump site revealed a history of organic waste disposal dating back to the 1970s. It also found that the company’s milk pond doesn’t have a liner or monitoring system, which is required for a groundwater discharge permit.

“It’s been a historic operation, so it’s quite possible that this water has reached ground water, we need to know lots of things about the ground water itself. Is it shallow? Is it deep? What’s its quality to begin with?” Mackey said.

We took the health and safety concerns from the Greenville residents to Grant Cardon, the Extension Soil Specialist at Utah State University’s College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences.

“Decomposing organic matter is going to release a lot of various nutrients that are stored in that material,” Cardon said.

He says milk is made up of a lot of fat and protein and when it decomposes it releases nitrogen.

“Nitrogen probably being, in my mind, one of the most concerning. Just because once it gets beyond the site, whether that be through ground water contamination deep through leaching, or moving through the storm water through surface water, a couple of things would be of concern,” Cardon said.

He said excess nitrogen in a surface water can cause algal blooms and anoxic conditions, which would cause difficulties with aquatic life and other things if it takes up all the oxygen. If nitrogen leeches through the soil, then it becomes a threat to human life.

“Deep through the soil, any contact with ground water, if that were to happen, nitrate becomes a livestock and human drinking water concern. It can alter the ability of the blood to carry oxygen and those kinds of things if it’s ingested,” Cardon said. He said dairy farmers have been dumping organic waste on soil for generations, but as communities grow and development spreads, farmers have to keep up with safety and regulation.

“You would want to set up observation wells and other things around just to monitor where that plum of movement is within the profile so you’re ensuring you’re not pushing it into local groundwaters,” said Cardon.

In a statement, Dairy Farmers of America acknowledged the recent increase in milk dumping in Beaver County, saying they “appreciate the concerns that have been brought to our attention,” and that they’ll work with the state to “ensure that we are following all applicable regulations.”

Dairy Farmers of America statement on milk application in Beaver County by LarryDCurtis on Scribd

But Cooney wants to know why the company initially ignored his concerns.

“We’ve called and complained and everything,” Cooney said. He and his neighbors worry that Dairy Farmers of America have put their safety at risk, and they want soil testing done immediately to determine if it’s contaminated.

“I want some remediation answers. I’m not going to listen to them say, ‘Well, we can look into it, blah, blah, blah,’ No! I want a detailed plan, okay. ‘Here’s what we’re going to do, and we’re going to drill and see how far we have to go,’ ” Meadows said.

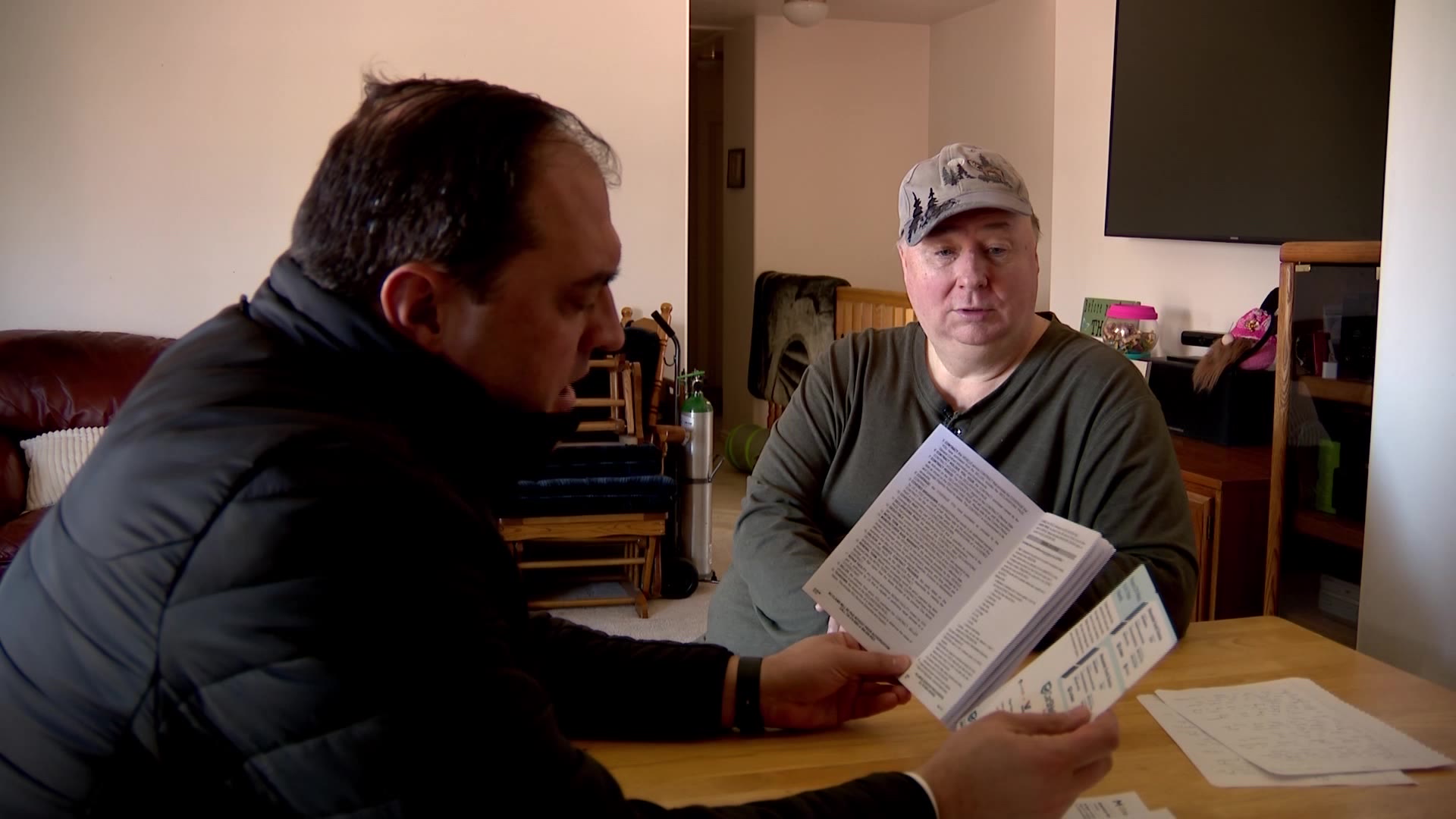

Neighbors Russell Meadows (L) and Dustin Cooney (R) are concerned by milk dumping happening near their homes in Greenville, a small community in Beaver County. (Josh Szymanik, KSL TV)

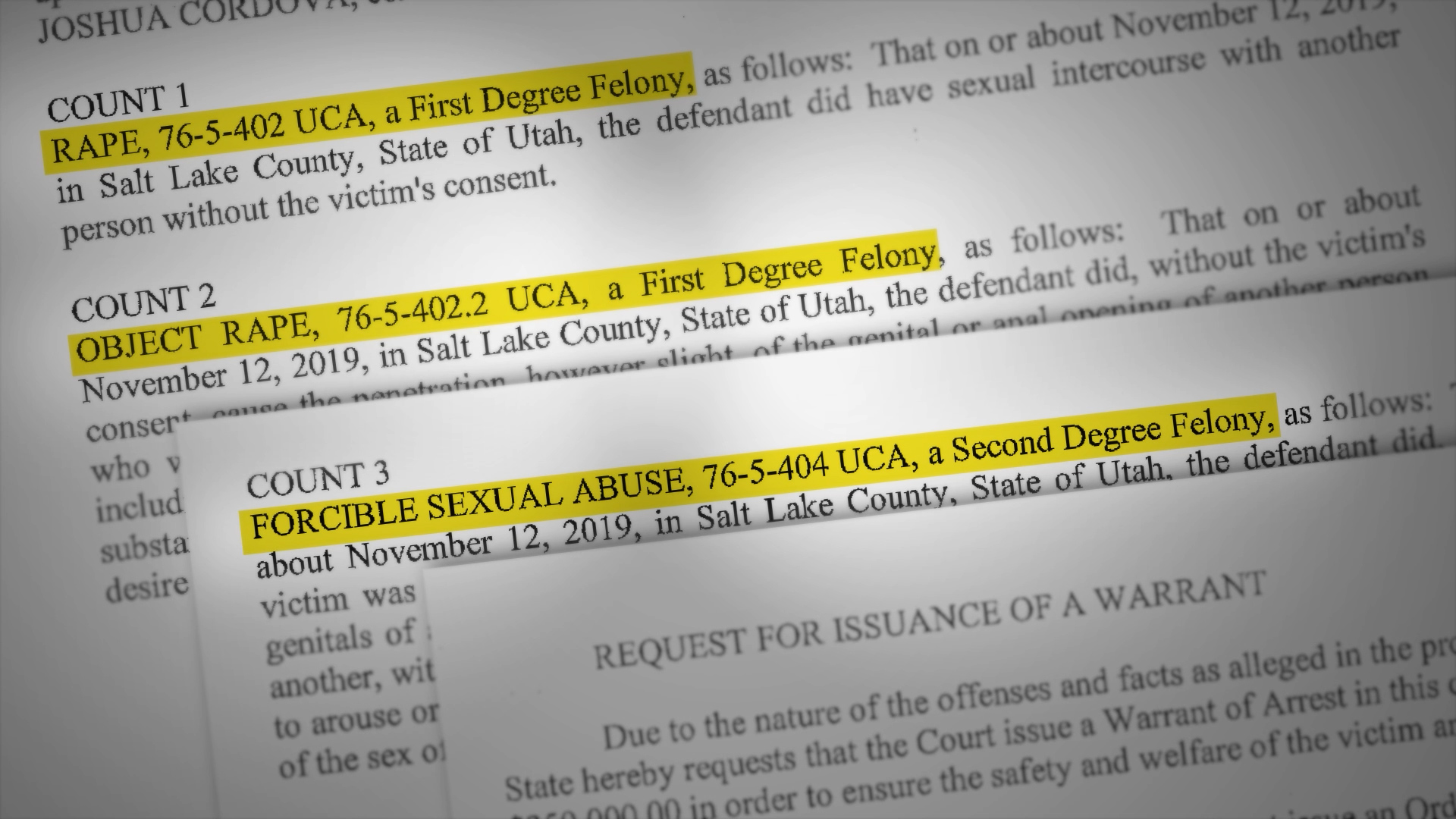

On Aug. 15, the Utah Division of Environmental Quality and Division of Water Quality issued a warning letter to Dairy Farmers of America that reads in part, “The practices observed by DWQ during the inspection represent a non-permitted potential discharge of pollutants to waters of the state.”

Per that letter, DFA is required to submit an application for a groundwater discharge permit within 90 days. And if it’s determined that ground water has been impacted, DFA must report it within 24 hours and provide a “corrective action plan within 30 days to assess the degree and extent of contamination and to minimize discharges in a way that is protective of human health and the environment.”

Utah Department of Environmental Quality warning letter by LarryDCurtis on Scribd

“The industry, as I understand it, is working on a plan,” Mackey said. “We’ve asked them to put together a groundwater permit in 90 days so there is scientific and engineering data that needs to be collected, they need to study their practices as well as the history of what’s been going on. Then come forward with a plan for how they’re going to prevent contaminating waters of the state.”

Mackey says if Dairy Farmers of America fails to meet these requirements, formal enforcement action could be taken. He says the company is already being cooperative and he’s hopeful enforcement won’t be necessary.

“I think this is something that will cause them to reevaluate this practice and either they’ll decide this is acceptable and permittable or they’ll change their practice.”