Utah reaches annual snowpack normal 2 months early. What happens next?

Feb 6, 2023, 5:25 PM | Updated: 9:06 pm

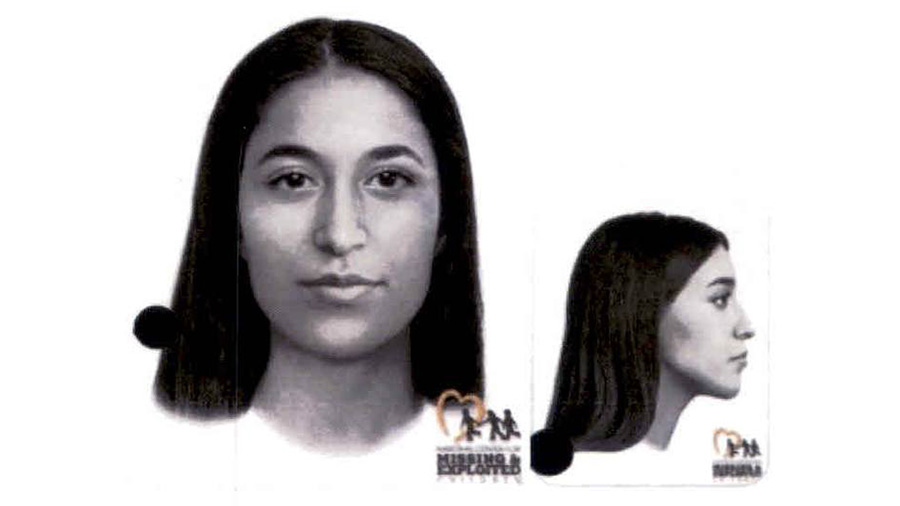

FILE: The snow pack that feeds the Great Salt Lake is showing much better promise for a better water year in 2023 (Alex Cabrero/KSL TV)

(Alex Cabrero/KSL TV)

SALT LAKE CITY — This weekend’s storm pumped more than one foot of snow in parts of the Cottonwood canyons, and helped Utah’s mountain snowpack reach its seasonal normal along the way.

The National Weather Service reported that one site near Brighton received 13 inches of snow, as of early Monday. About another half-foot of snow is expected in the state’s mountains Monday, according to KSL meteorologist Matt Johnson. However, the snow showers are expected to clear out by the afternoon, aside from some lingering showers at the highest mountain peaks, he said.

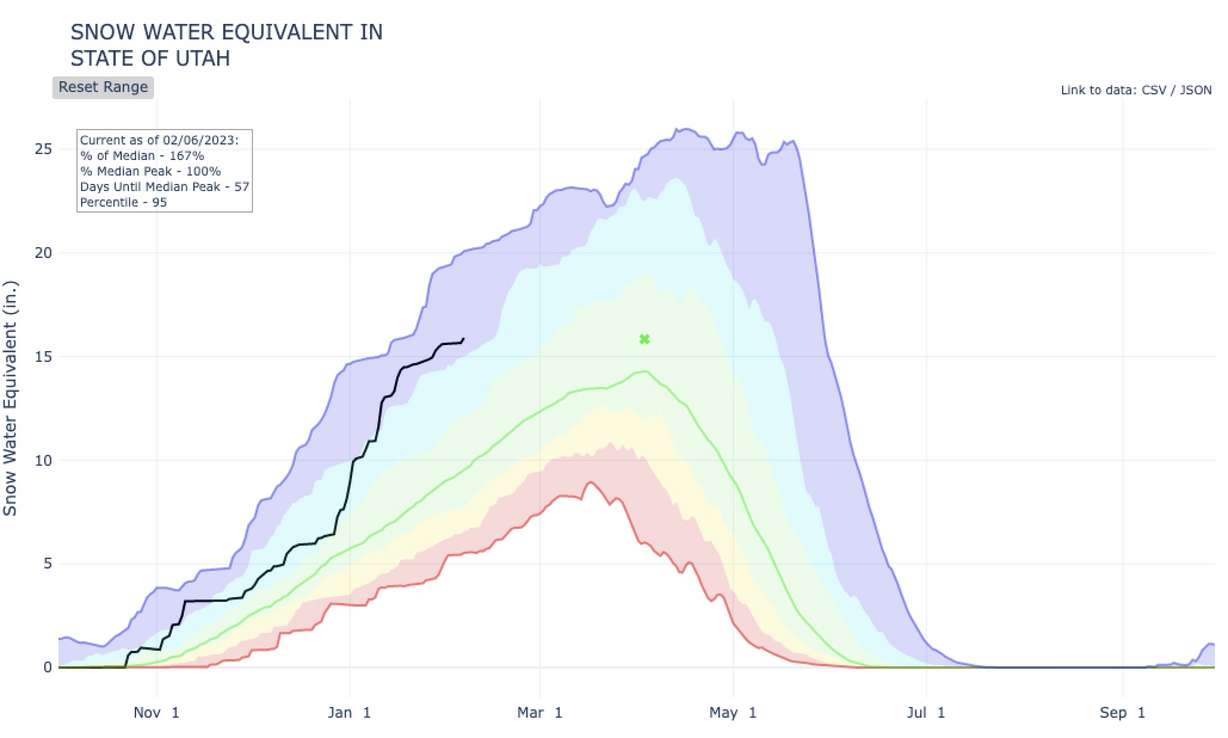

Utah’s snowpack — the amount of water within the snow — has jumped to 15.9 inches with the freshly-fallen snow, according to Natural Resources Conservation Service data, accessed at noon Monday. The figure dates back to the start of the water year on Oct. 1, 2022.

The state’s normal annual snowpack collection is 15.8 inches; however, Utah’s snowpack failed to exceed 12.1 inches over the previous two water years.

What’s more, the statewide total reached the annual mark about two months ahead of schedule. Utah’s snowpack normally reaches 15.8 inches in early April before the snowpack begins to melt during the spring, slowly refilling the state’s depleted lakes and reservoirs.

“(It) is really exciting,” said Laura Haskell, drought coordinator with the Utah Division of Water Resources, regarding the snowpack data. “We are happy to see that, very happy.”

That said, she cautions this year’s snowpack likely won’t fix all of Utah’s water woes.

Eying the perfect spring conditions

State water managers are still cheering for storms to pad the statistics, but they are also shifting their focus onto spring weather now that winter has completed its assignment. That is, they want to see the perfect conditions that will ensure that all of the water in the mountain snow ends up in lakes and reservoirs.

They don’t want the snowpack to melt too quickly because it will lead to flooding, and they don’t want it to melt too slowly because it’ll end up in the ground instead of in rivers and streams that dump into lakes and reservoirs. Haskell refers to it as the “Goldilocks conditions,” where temperatures are just right in April and May for the process to work as efficiently as possible.

“There’s this sort of perfect (scenario) where it melts a little then it sort of freezes overnight,” she said. “A lot of it really is up to Mother Nature — how it melts and how much we get to see in the reservoirs.”

Water supply forecasts at the moment have Utah’s final snowpack ending up anywhere between 110% and 130% of the normal, which would be a big boost for the state’s reservoirs and also the Great Salt Lake.

Utah’s reservoir system — excluding Lake Powell and Flaming Gorge — dropped to as low as 41.5% capacity in October. The system is now listed at about 49% capacity. The Great Salt Lake gained 1 foot in elevation over the past few months but remains at 4,189.2 feet elevation, about 11 feet below its average recorded level

Why water challenges still exist

The forecast also means that even if Utah receives the desired “Goldilocks conditions” this spring, there is still a large deficit to overcome. Utah’s reservoir system is currently about 11 percentage points below where it typically should be in early February, according to Utah Division of Water Resources data.

The difference between the current average and the normal average is roughly the same size as Bear Lake at full capacity, Haskell said. At the same time, the latest U.S. Drought Monitor report still lists three-fourths of Utah in at least a severe drought, including 18.5% in extreme drought.

That means Utahns will likely hear about ways to reduce water consumption again this summer — even with an above-normal snowpack this water year.

“We still need to be water-wise,” Haskell said. “This is an opportunity to be careful with our water use so can refill these reservoirs. … We can choose how we use the water once it’s in our reservoirs. We can choose to deplete it not as quickly.”