Joyce Yost’s Rape Case First Prosecuted Without Victim To Testify

Apr 20, 2021, 10:27 PM | Updated: Apr 21, 2021, 12:16 am

FARMINGTON, Utah — In a case of he-said-she-said, who is a judge or jury to believe when “she” isn’t actually there to say anything?

The disappearance of Joyce Yost 10 days before she was scheduled to testify in a felony kidnapping and sexual assault trial left prosecutors in an unusual position. They faced the task of trying the case without a victim in court acting as the accuser and key witness.

“It was the first time we prosecuted a rape case without a victim in the state of Utah,” former Clearfield police detective William Holthaus said. “We were pretty nervous.”

The unconventional case is a pivotal point in the second season of KSL’s investigative podcast series COLD, which focuses on Yost’s disappearance.

Background of the Case

Holthaus had interviewed Yost on the morning of April 4, 1985, just a couple hours after she’d first reported being kidnapped and raped by a man she did not know. Holthaus then identified Douglas Anderson Lovell as a suspect and arrested him later that same day.

Yost went on to testify at a preliminary hearing two months later, not realizing Lovell was then secretly plotting to have her killed. Her testimony resulted in Utah 2nd District Court Judge Rodney Page advancing the case to arraignment and scheduling a trial for August 20, 1985.

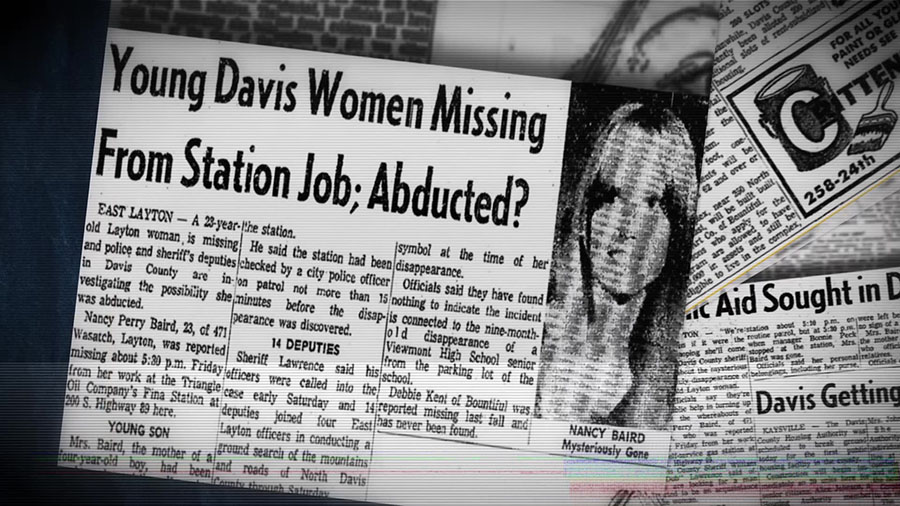

Yost disappeared on the night of August 10, 1985 and efforts to locate her in time for the trial failed. Investigators at the time suspected foul play and believed Lovell was responsible, but were unable to prove it.

“At the time I didn’t think he was, frankly, dumb enough to do it himself,” Holthaus said in a May, 2020 interview for COLD.

Strength of the Evidence

The very nature of rape and sexual assault cases — which often involve just a single suspect and victim and no outside witnesses — mean prosecutors most often build their cases around the testimony of the victim.

There were no direct witnesses to Yost’s sexual assault, though she had told her sister what’d happened immediately afterward. Holthaus had also observed evidence which supported Yost’s account, including her own physical injuries.

“I believed what she was saying based on the evidence that I first saw,” Holthaus said.

Utah 2nd District Court issued a subpoena commanding Joyce Yost to appear for the kidnapping and sexual assault trial against Douglas Lovell. Yost had disappeared months earlier and did not respond to the subpoena.

Without Yost there to testify herself, prosecutors requested a delay in the trial. Deputy Davis County Attorney Brian Namba, the lead prosecutor on the case, had to consider whether he could secure a conviction if Yost didn’t return.

Namba pressed forward with the case and the court rescheduled the trial for Dec. 11, 1985. The court also issued a subpoena to Yost, which went unanswered. Lovell’s defense attorney insisted that the circumstances surrounding her disappearance not be disclosed to the jurors. Namba and the judge agreed they would only be told she was unavailable to testify for reasons unrelated to the case.

“Which turns out not to be true,” Namba said, “but that was our stipulation in order to allow the jury to deliberate fairly on the rape issue.”

Testimony by Proxy

At the trial, Lovell testified that Yost had willingly consented to have sex with him. This was contrary to what Yost had said both in interviews with police as well as at the preliminary hearing.

To counter this, Namba employed a tactic that was relatively untested at the time. He introduced Yost’s testimony from the preliminary hearing as evidence, having an attorney’s office secretary named Marily Gren read the transcript in Yost’s place.

“The danger of doing that kind of a case is that [the jurors] blow off the testimony thinking ‘well, she didn’t even think enough of it to come here herself,’” Namba said.

Former Davis County Attorney’s Office secretary Marily Gren holds a transcript of Joyce Yost’s preliminary hearing testimony during an interview for COLD on June 12, 2020. (Photo: Dave Cawley, KSL Podcasts)

Lovell’s defense attorney objected on the grounds it was hearsay and deprived Lovell of his constitutional right to confront his accuser. Judge Rodney Page overruled the objection, noting Yost’s prior testimony had been subjected to cross-examination during the preliminary hearing and as such was exempted from a rule barring the admission of hearsay testimony.

The jury convicted Lovell, largely on the strength of Yost’s prior testimony and Gren’s presentation of it.

“You have to engage the jury so that they feel [Yost’s] presence,” Namba said. “I think [Gren] really accomplished that.