Voyager 1 is sending data back to Earth for the first time in 5 months

Apr 22, 2024, 6:24 PM

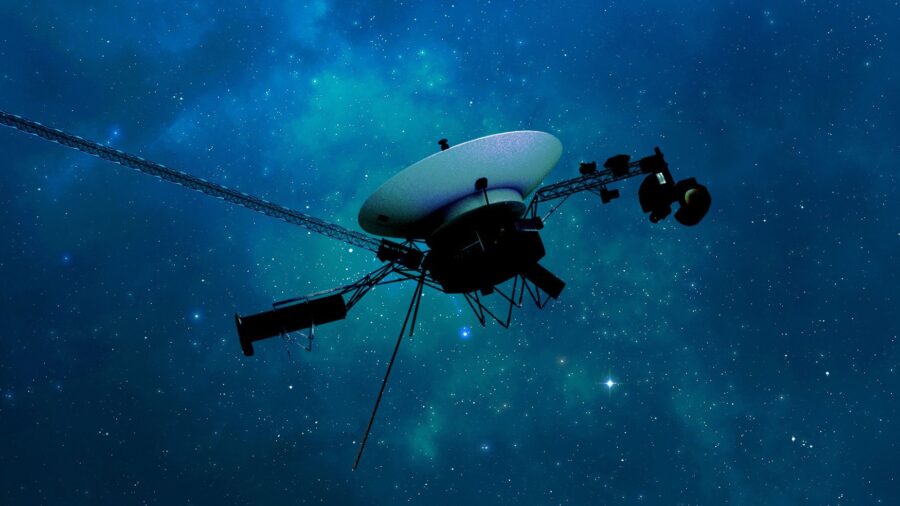

An artist's illustration depicts Voyager 1 as it travels through interstellar space, or the space between stars. (NASA/JPL-Caltech via CNN Newsource)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech via CNN Newsource)

(CNN) — For the first time in five months, NASA engineers have received decipherable data from Voyager 1 after crafting a creative solution to fix a communication problem aboard humanity’s most distant spacecraft in the cosmos.

Voyager 1 is currently about 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away, and at 46 years old, the probe has shown multiple quirks and signs of aging in recent years.

The latest issue experienced by Voyager 1 first cropped up in November 2023, when the flight data system’s telemetry modulation unit began sending an indecipherable repeating pattern of code.

Voyager 1’s flight data system collects information from the spacecraft’s science instruments and bundles it with engineering data that reflects its current health status. Mission control on Earth receives that data in binary code, or a series of ones and zeroes.

But since November, Voyager 1’s flight data system had been stuck in a loop. While the probe has continued to relay a steady radio signal to its mission control team on Earth over the past few months, the signal did not carry any usable data.

The mission team received the first coherent data about the health and status of Voyager 1’s engineering systems on April 20. While the team is still reviewing the information, everything they’ve seen so far suggests Voyager 1 is healthy and operating properly.

“Today was a great day for Voyager 1,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager project scientist at JPL, in a statement Saturday. “We’re back in communication with the spacecraft. And we look forward to getting science data back.”

The breakthrough came as the result of a clever bit of trial and error and the unraveling of a mystery that led the team to a single chip.

Troubleshooting from billions of miles away

After discovering the issue, the mission team attempted sending commands to restart the spacecraft’s computer system and learn more about the underlying cause of the problem.

The team sent a command called a “poke” to Voyager 1 on March 1 to get the flight data system to run different software sequences in the hopes of finding out what was causing the glitch.

On March 3, the team noticed that activity from one part of the flight data system stood out from the rest of the garbled data. While the signal wasn’t in the format the Voyager team is used to seeing when the flight data system is functioning as expected, an engineer with NASA’s Deep Space Network was able to decode it.

The Deep Space Network is a system of radio antennae on Earth that help the agency communicate with the Voyager probes and other spacecraft exploring our solar system.

The decoded signal included a readout of the entire flight data system’s memory.

By investigating the readout, the team determined the cause of the issue: 3% of the flight data system’s memory is corrupted. A single chip responsible for storing part of the system’s memory, including some of the computer’s software code, isn’t working properly. While the cause of the chip’s failure is unknown, it could be worn out or may have been hit by an energetic particle from space, the team said.

The loss of the code on the chip caused Voyager 1’s science and engineering data to be unusable.

Since there was no way to repair the chip, the team opted to store the affected code from the chip elsewhere in the system’s memory. While they couldn’t pinpoint a location large enough to hold all of the code, they were able to divide the code into sections and store it in different spots within the flight data system.

“To make this plan work, they also needed to adjust those code sections to ensure, for example, that they all still function as a whole,” according to an update from NASA. “Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the (flight data system) memory needed to be updated as well.”

After determining the code necessary for packaging Voyager 1’s engineering data, engineers sent a radio signal to the probe commanding the code to a new location in the system’s memory on April 18.

Given Voyager 1’s immense distance from Earth, it takes a radio signal about 22.5 hours to reach the probe, and another 22.5 hours for a response signal from the spacecraft to reach Earth.

On April 20, the team received Voyager 1’s response indicating that the clever code modification had worked, and they could finally receive readable engineering data from the probe once more.

Exploring interstellar space

Within the coming weeks, the team will continue to relocate other affected parts of the system’s software, including those responsible for returning the valuable science data Voyager 1 is collecting.

Initially designed to last five years, the Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, launched in 1977 and are the longest operating spacecraft in history. Their exceptionally long life spans mean that both spacecraft have provided additional insights about our solar system and beyond after achieving their preliminary goals of flying by Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune decades ago.

The probes are currently venturing through uncharted cosmic territory along the outer reaches of the solar system. Both are in interstellar space and are the only spacecraft ever to operate beyond the heliosphere, the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond the orbit of Pluto.

Voyager 2, which is operating normally, has traveled more than 12.6 billion miles (20.3 billion kilometers) from our planet.

Over time, both spacecraft have encountered unexpected issues and dropouts, including a seven-month period in 2020 when Voyager 2 couldn’t communicate with Earth. In August 2023, the mission team used a long-shot “shout” technique to restore communications with Voyager 2 after a command inadvertently oriented the spacecraft’s antenna in the wrong direction.

The team estimates it’s a few weeks away from receiving science data from Voyager 1 and looks forward to seeing what that data contains.

“We never know for sure what’s going to happen with the Voyagers, but it constantly amazes me when they just keep going,” said Voyager Project Manager Suzanne Dodd, in a statement. “We’ve had many anomalies, and they are getting harder. But we’ve been fortunate so far to recover from them. And the mission keeps going. And younger engineers are coming onto the Voyager team and contributing their knowledge to keep the mission going.”