As Utah’s meteorological summer closes on a wet note, what’s in store for fall?

Aug 22, 2023, 5:13 PM | Updated: 11:43 pm

SALT LAKE CITY — What started as a particularly dry summer in Utah, after a record-breaking snow collection season, has quickly changed over the past few weeks, and that trend could continue into fall, according to a long-range forecast published last week.

The National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center released its first three-month outlook for September, October, and November, the months that compose meteorological fall, on Thursday.

The forecast, based on a mixture of current trends and historic data in similar situations, lists all of Utah in “equal chances,” meaning there’s no clear signal whether it will be wetter, drier or close to normal throughout the duration of the season. All three scenarios have about a 33% probability of coming to fruition.

These maps show the long-range probabilities for temperature, left, and precipitation, right, for the meteorological fall months of September, October and November. Utah is listed as having a higher probability of above-normal temperatures, but its precipitation expectations aren’t clear. (Photo: National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center)

The center’s outlook lists Utah as having a 40% to 50% probability of above-normal temperatures, as well. The state will still continue to gradually cool down as a result of the changing seasons.

Behind the uncertainties

The Climate Prediction Center’s outlook, released a few weeks ahead of the season’s start, also listed most of the state as having equal chances when it comes to precipitation because the emerging El Niño oceanic pattern led to speculation that Utah’s monsoon season would be delayed and possibility diminished.

That is how Utah’s summer ultimately started, as its June and July statewide precipitation average, combined, ended up 0.45 inches below the 20th-century normal, according to National Centers for Environmental Information data. Meteorological spring ended on a dry note, as well.

It switched at the beginning of August, as scattered monsoonal storms produced an entire month’s and season’s-worth of rain right off the bat in several communities. These types of storms are expected to continue through the end of August and into September, according to the Climate Prediction Center’s more near-term outlooks.

But El Niño is also a driving factor behind the precipitation uncertainties throughout fall, says John Wilson, a meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Salt Lake City office. This is when the Pacific trade winds weaken, sending warmer water toward the Western U.S. and adjusting the Pacific jet stream.

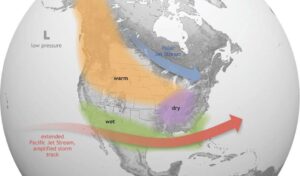

This graphic shows the historical trend of an El Niño pattern on North America. Meteorologists believe that this pattern will return for this winter. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)The traditional El Niño model produces all sorts of scenarios in Utah weather as compared to more predictable outcomes in other parts of the country, much like La Niña. This pattern strengthens during the winter.

“There’s either a strong signal, somewhat of a moderate signal or a weak signal depending on where you are in the country, with what El Niño generally does. Unfortunately, across Utah, it’s a rather weak signal,” he said. “It can really go either way.”

In turn, the fall outlook says every precipitation outcome is in play for the season. El Niño’s signal is much stronger in other parts of the West, generally leading to drier-than-normal conditions in the Pacific Northwest and wetter-than-normal conditions in the Southwest. This year’s fall outlook calls for drier conditions in the Pacific Northwest, while most of the Southwest is also listed as having equal chances.

Why fall matters in Utah

Meteorological fall certainly isn’t as important for Utah’s water supply as the winter, but it still can play a key role. It’s normally when precipitation returns after the drier summer, improving soil moisture conditions ahead of the next snowpack buildup. This leads to a more efficient spring runoff.

Autumn is already off to a good start before it even begins because Utah’s soil moisture levels are well above the median for late August as a result of last winter’s record snowpack and August precipitation. Utah’s reservoir system remains 79% full after topping out at 86% last month following this spring’s efficient runoff.

Jared Hansen, project manager for the Central Utah Water Conservancy District, said the recent monsoonal moisture is helping keep reservoirs full by reducing the demand for irrigation water, as well.

“We’re set up great for next year,” he said.

Wilson adds normal fall precipitation can also lessen wildfire risks. Utah’s wildfire season typically ends in October, but it had become more year-round in recent years, with a mixture of drought and increasing seasonal temperatures.

Meanwhile, it’s still too early to know what this fall means in terms of winter, other than the probabilities are low that Utah will repeat its record snowpack, Wilson said. But that, too, is a bit of a mystery right now — much like the fall outlook.

“We can’t really say with confidence that we will be very wet, very dry or somewhere in between,” he said. “There’s just a lot of uncertainty.”

As soon as the snow starts to fall, water managers like Hansen will have to begin managing the reservoirs on a daily basis because of how quickly the reservoirs rebounded. It’s a scenario nobody could have predicted this time last year.

That means some river levels will be higher this winter as teams release water to avoid flooding risks.

“Hopefully, we can get some of (the reservoir) water moved on to the Great Salt Lake and try to fill some of that deficit,” Hansen said. “We want to do it in a controlled manner. We don’t want to cause flooding. We don’t want to do damage to the natural environment.”