SALT LAKE CITY — The advice from a member of the International Olympic Committee delegation in Utah this week to inspect venues for a 2034 Winter Games sounded contradictory at first: Don’t be in a rush to put plans in place, but don’t wait to take advantage of the opportunity.

“Let’s not hurry on this. But then, be bold and ambitious,” the IOC’s Olympic Games executive director, Christophe Dubi, said during an invitation-only community forum held in the Eccles Theater lobby last week, insisting, “it’s urgent not to start too early” to organize a Winter Games.

The 2034 Winter Games could be formally awarded to Utah on July 24, the state’s Pioneer Day, at an IOC meeting in Paris ahead of the 2024 Summer Games. That’s a decade in advance, three years sooner than Games used to be awarded.

Salt Lake City, named the IOC’s preferred host for 2034 late last year, was visited this week by members of the IOC’s Future Host Commission along with IOC executives and staff. While they heaped praise on Utah’s venues and passion for the Olympics, Dubi offered some counsel.

The advice from a member of the International Olympic Committee delegation in Utah this week to inspect venues for a 2034 Winter Games sounded contradictory at first: Don’t be in a rush to put plans in place, but don’t wait to take advantage of the opportunity. (Mark Less, KSL TV)

“You have all it takes. You have the venues and you have the people. Once you have that, you have the ingredients to deliver the Games,” he said, adding that waiting to focus on operations allows time for new developments to emerge, especially in artificial intelligence.

The ability to “deliver a lot” should inspire Utahns to emulate organizers of this summer’s Olympics who “started very early with this ambition that the Games should be France’s Games,” he said, suggesting Utah could extend efforts to involve more youth in sports across the United States.

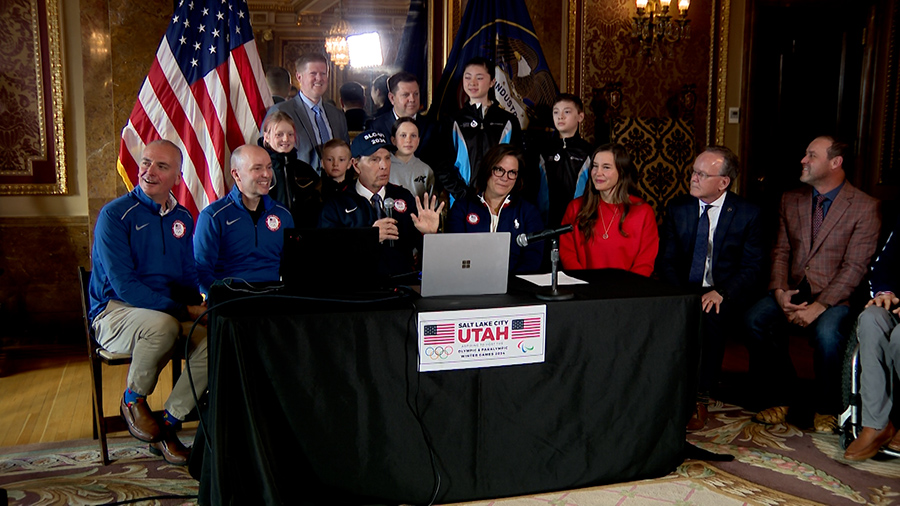

Jacqueline Barrett, the IOC’s Future Olympic Games Hosts director, told reporters at a news conference held at a downtown social club Saturday, that the “great capability here, great confidence and level of readiness” in Utah could help elevate future Winter Games.

“There’s a possibility to think wider now, to think how could the Olympic Winter Games here in 2034 be transformative,” Barrett said.

What the IOC wants to avoid

In an interview Saturday with the Deseret News before the delegation left Utah, Dubi drew the line at linking Olympic budgets with infrastructure and other projects that aren’t necessary to host even though that’s been the ambition of many past host cities.

“I think it’s finding the right balance between the positive energy that the Games can generate, the acceleration for some of the projects that would be meaningful for a community over a long period of time while not counting all of these on a Games budget,” he said.

Looking at infrastructure development as an expense of hosting an Olympics is the issue, Dubi said. “That has happened quite a lot in the past, where you would find roads, bridges or whatever infrastructure on the cost of the Games. That needs to be avoided.”

He said Utah’s bidders already understand such projects would be outside their scope. In the United States, the Olympics are privately organized, paid for with revenues largely from the sale of sponsorships, broadcast rights and tickets. The most recent proposed price tag to put on a 2034 Games is $2.45 billion.

Utah leaders are already looking at what can get done for the state if there’s another Olympics coming.

Natalie Gochnour, director of the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute at the University of Utah, told the Deseret News any efforts to organize an Olympics now “might be for naught because the world is changing so much,” in terms of technology, transportation and human capital.

But that doesn’t have to mean losing the momentum that would be generated by getting another Games. That’s where ambition comes in, to drive a shift to what Gochnour called “superstructure” projects.

“A perfect example would be Great Salt Lake elevation levels. We can’t wait on that. That’s an urgent concern today,” she said, adding it’s one of the issues facing the state that “we want to make progress on before the eyes of the world are here.”

Another Winter Games, Gochnour said, “creates a lot of alignment and incentive for us to be our best selves. So we’re going to focus on the Great Salt Lake, with or without the Olympics. But with the Olympics? It’s just that extra push.”

The three extra years that Utah would have “to focus on that superstructure, that’s a gift to us,” she said. “It will help create alignment and give us extra fuel for the momentum that we already feel.”

An IOC committee visiting Utah to check on its readiness to host the Winter Games, headed for home on Saturday. (Mark Less, KSL TV)

What projects ‘need to happen now?’

Fraser Bullock, president and CEO of the Salt Lake City-Utah Committee that’s behind the bid, said the staffing for organizing another Winter Games would be “very modest to begin with,” with much of the detailed work not getting underway for another five years.

“But there are two things that need to happen now,” Bullock said. One would be the organizing committee’s community initiatives aimed at involving children in sport. The other is getting going on “some big infrastructure projects that do take some time,” he said.

Those include the Kimball Junction exit off I-80, the gateway to the nearby Utah Olympic Park as well as the Deer Valley and Park City Mountain Resort ski areas set to host Winter Games events, Bullock said.

Other projects are already being tied to another Olympics, just as the expansion of I-15 and other transportation projects were for the 2002 Winter Games. The Utah Transit Authority even held a news conference at a TRAX stop for a reserved train transporting the IOC delegation, touting the agency’s extensive plans for bus, light rail and train systems through 2030 and beyond.

University of Utah President Taylor Randall told the Deseret News the Olympics are “almost a perfect partnership” for the campus, which once again would be the site of the opening and closing ceremonies in Rice-Eccles Stadium as well as the housing for athletes.

“The Olympics has been a catalyst for growth and reputation at the University of Utah. In 2002, we were able to build an Olympic Village (for athletes) which now houses many of our students. Similar investments would be made that will be very complimentary to the growth of the university,” he said.

“One of the unique things that these Games organizers are trying to do is to create an Olympic legacy that exists afterwards,” Randall said. “There are a number of ideas. For example, the University of Utah and our mental health capabilities, to be able to focus on the mental health of athletes and the performance requirements of athletes is part of a legacy we could leave.”

Former Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt, whose decade as governor ended in 2003, when he accepted a post with the George W. Bush administration, recently urged leaders to start taking advantage of the “huge amount of back pressure that will allow you to get a lot of things done that you could never get done in their absence.”

What Salt Lake City and Utah leaders say about another Olympics

Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall made a point of telling the IOC that the city’s ambitions already align with what would benefit another Winter Games.

“It’s not that the Games are going to make something happen that we weren’t going to do anyway,” she said during the bid committee’s initial presentation to the IOC delegation, pledging the city will remain committed to environmental goals even as the downtown population is set to double.

The mayor pitched projects aimed at attracting more families downtown including “a pedestrianization of this Main Street corridor” that would include a 100 South connection to the Salt Palace Convention Center, “a green loop that encircles this downtown core” to give children a place to play, and bringing technology companies closer to the University of Utah.

Mendenhall said during the community forum that “one of the greatest ways to feel like you’re a part of something is to know what direction that something is going in. When we commit to a Games, we have a firm deadline.”

She also promised Utahns will continue to be asked what they want to see from another Olympics, labeling youth as the top priority in a state that’s “good at raising families.”

There wasn’t talk publicly about specific goals for the Games from state officials during the visit even though it’s Gov. Spencer Cox, not the Salt Lake City mayor, who would sign the host agreement with the IOC.

That’s different from 2002, when the IOC dealt directly with city leaders, who had to seek indemnification from the state. This time around, legislation passed by Utah lawmakers in 2023 spells out that the state would be financially responsible for an Olympics should revenues fall short.

Lt. Gov. Deidre Henderson, who stepped in for the governor at the initial presentation because of the first lady’s surgery, spoke about the personal impact hosting an Olympics can have on Utahns, “The Olympics is as much a part of who we are as anything else in our state,” the lieutenant governor said.

Nubia Peña, director of the Utah Division of Multicultural Affairs, emphasized the state’s growing minority population at the community forum, promising a “welcoming community where people feel loved, seen and valued.”

Another Olympics in Utah, Peña said, would be for everyone, not “only for the elite.”