Utah universities ‘ignored’ her report of rape against a football player, student says, leaving others vulnerable

Dec 21, 2021, 11:42 AM | Updated: Jun 19, 2022, 10:00 pm

SALT LAKE CITY – Marissa Root knew she’d need help to get through the semester.

The Utah Valley University student had gone to the hospital just a few weeks earlier, where medics evaluated her, collected DNA evidence and directed her to speak with her school about resources to help her cope.

“I had no idea how I was going to finish my classes,” Root recalled recently in an interview with KSL investigators. “I couldn’t get out of bed.”

She hoped to get counseling and extra time for coursework. But Root says the UVU’s Title IX office — tasked with investigating reports of sexual assault and harassment at her own college in Orem — turned her away when she reported being raped by a University of Utah football player in 2019, referring her to her alleged perpetrator’s school instead.

An employee in University of Utah’s Title IX Office, dissuaded her from filing an official complaint against the player, Root contends, telling her the school’s obligations were to the football player and the school “may be limited” in addressing her complaint since she wasn’t a student there.

The football player stayed on the team until after the school learned police were investigating, Root claims in a new lawsuit against the universities and the Utah System of Higher Education, (USHE) which governs Utah’s eight public colleges.

She says the institutions left others at risk of being victimized by the same student athlete and violated Title IX, the federal law barring sex discrimination in education.

KSL does not typically name victims of alleged crimes. Root, now 26, chose to use her name.

Root contends USHE has the authority to coordinate between colleges when a student is sexually assaulted but does not do so. As a result, she and other students “are being unjustifiably and illegally ignored,” the suit states.

Root has not named her alleged assailant publicly. But last March, prosecutors filed criminal charges against Sione Lund, 23, a former University of Utah linebacker, tied to an alleged assault that took place at a small gathering at his home on Sept. 15, 2019. That’s the same day Root said in her lawsuit she was victimized by a linebacker on the university’s football team at a small gathering at a player’s home.

UVU employees encouraged her to report the incident to the University of Utah to “scare the football player from ‘actually violently raping someone,’” her lawsuit says.

But Root said the investigator within the Office of Equal Opportunity at the University of Utah did not seem interested in learning who the football player was.

“They didn’t ask me his name,” Root said. “They should have been very concerned that their campus might not be safe for other people.”

The University of Utah disagreed in a Tuesday statement to KSL, saying, “the UVU student made it clear she did not wish to share the name of the alleged assailant with (Office of Equal Opportunity) staff and told them she had received medical care, contacted local police and consulted with an attorney.”

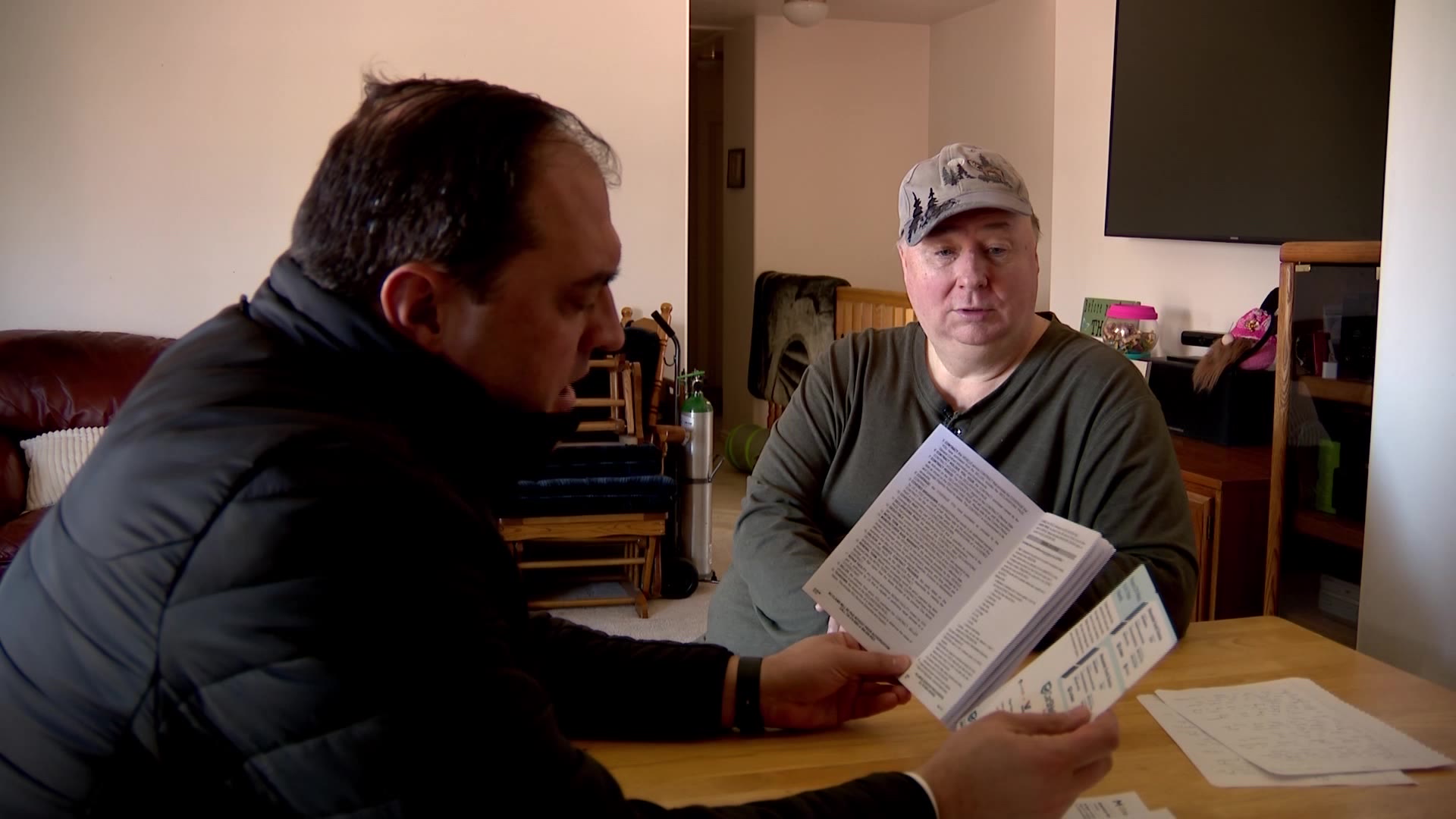

Not so, said Root’s attorney, Michael Young. The very reason Root reported to the university was to help it protect other women from the player. Young added: “it is troubling the university continues to ignore the safety of women and refuses to learn from past failures.”

The two universities aren’t saying whether they have an agreement to handle cases like Root’s. Nationally, many schools in close proximity do so, said Laura Dunn, a Washington, D.C.-based Title IX expert and attorney.

“If there are campuses that are right next to each other, and you know there’s issues of sexual violence between them and you’re not creating policies and procedures, I really do think that’s negligent,” Dunn said. “Without a concentrated effort, you’re not going to have a clear path.”

When students experience sexual violence, their own universities have a duty under Title IX to provide supportive measures, Dunn said, and to try to accommodate the trauma that may affect their studies.

Dunn is not involved in the lawsuit but reviewed Root’s legal claims against the schools for KSL.

“There should have been an analysis or reasoning provided for why they did or did not have an obligation under Title IX, so that the survivor could figure out with legal counsel, is that correct? Or are they misunderstanding what Title IX says?” she said.

Student athletes, she continued, “should be held, not just to the same standards, but arguably, to higher standards, because they’re representing the school in the public space.”

The University of Utah said it responds to every report of sexual assault with urgency and great care, following its nondiscrimination policies and guidelines.

The Office of Equal Opportunity, which conducts Title IX investigations, held a training about consent and prevention for the football players the same month, the university said. Its employees learned the name of the alleged assailant when it became aware of the Unified police investigation in February 2020, then spoke with the player and his attorney.

“The alleged assailant was suspended from the football program in February 2020 as a result of the pending criminal case,” the university’s statement reads. The announcement of the discipline came the following month.

Utah Valley University spokesman Scott Trotter issued a statement saying, “we disagree with the claims in the lawsuit.”

The statement went on to say, “We take reports of sexual assault seriously and offer support services and resources to victims of sexual violence, regardless of where, when, or how such violence may have occurred.”

But Trotter declined to respond directly to Root’s claims, citing student privacy concerns.

Utah System of Higher Education spokeswoman Trisha Dugovic said the office and its universities “hold student safety as one of their top priorities, and we take all reports of alleged wrongdoing on our campuses with the utmost seriousness.”

The Salt Lake County District Attorney’s Office charged Lund in March with rape and forcible sodomy, both first-degree felonies, in Salt Lake City’s 3rd District Court.

His defense attorney Tara Isaacson noted Tuesday that her client cooperated in the investigation and told police the contact was consensual.

“He’s not playing football anymore,” Isaacson said. She declined to give details of his departure from the team.

The night of the alleged assault, Root told her friends she didn’t want to be alone with him, but he “isolated” her, the lawsuit states.

He’d made advances in the past, but she “never responded to his communications and kept the relationship amicable but distant,” the lawsuit says.

Prosecutors say that once they were alone in his room, Lund assaulted her as she told him to stop repeatedly and said that he was hurting her, charges state.

A public relations major, Root abandoned her plan to someday work with professional sports teams, she said. She’s too fearful of what could happen if the job required her to be alone with someone she can’t trust.

“There is no right way to grieve a situation like this,” Root said. “But over the last two years, I’ve learned that being quiet doesn’t help anything.

Have you experienced something you think just isn’t right? The KSL Investigators want to help. Submit your tip at investigates@ksl.com or 385-707-6153 so we can get working for you.